May is celebrated as Asian Heritage Month, and in honour of this occasion, we invited three Arts faculty members to share their favourite art and literature pieces from their culture that hold personal significance.

Art and literature form the foundation of one’s heritage and culture, influencing an individual’s values and identity. Dr. Tara Lee, Gu Xiong, and Dr. Mila Zuo reflect on how these pieces of art and literature are related to their lived experiences as Chinese-Canadians in our community. Their perspectives shed light on the invaluable takeaways of cross-cultural media.

Dr. Tara Lee

Lecturer in the School of Journalism, Writing, and Media

Dr. Lee teaches as a lecturer in the School of Journalism, Writing, and Media. She specializes in writing studies, Canadian literature, critical race studies, techno/new media studies, dystopian literature, and children’s and young adult literature. Additionally, Dr. Lee works as a freelance journalist, broadcaster, and copywriter.

Can you share with us a piece of art or literature that you feel reflects your experience as an Asian person in the UBC community and also celebrates your Asian Heritage? How has this piece impacted you personally or professionally?

Disappearing Moon Cafe by Sky Lee

I was born in Vancouver and I am a second-generation Chinese Canadian on my mother’s side and a fifth-generation Chinese Canadian on my father’s side. Growing up, my Chinese culture was always important to me but I didn’t think about my identity that deeply, nor my place within larger Chinese Canadian history. When I was an undergraduate, I took a Canadian Literature course with Dr. Glenn Deer, who opened my eyes to the works of Chinese Canadian writers. One of the texts that we covered was Sky Lee’s Disappearing Moon Cafe, a seminal Chinese Canadian novel. The struggles of the main character to confront her relationship with the Canadian nation-state, her familial allegiances, as well as the narratives of the past and present really resonated with me. That English course—and Lee’s novel—profoundly changed the trajectory of my academic career as well as my sense of my Asian Canadian subjectivity.

In what ways has your Asian heritage influenced your own artistic creations and/or research? Can you share any specific examples of how this has influenced your work?

My Asian heritage is a fundamental part of who I am, as well as how I perceive the world. My doubleness as an Asian Canadian, which also intersects me with my other identity markers, keeps me productively in motion. In my freelance writing for various publications, this in-betweenness has meant that I seek out voices that are often overlooked by mainstream media and try to promote cross-cultural communication and collaboration. Within the classroom as well as in my course design, my Asian Canadian perspective also plays a significant role. I encourage students to engage with hegemonic structures and to consider how their own subject positions influence their readings of various texts and their own production of knowledge. Often, I will assign articles and texts that are written by authors/researchers of Asian heritage and that treat concerns relevant to Asian cultures and identities. Ultimately, it is impossible for me to separate my Asian heritage from both my creative as well as pedagogical practices.

How do you see the role of art and literature in promoting Asian culture and heritage?

Art and literature are fundamental for grappling with and representing the complexities and ambiguities of Asian cultures and heritage. The term “Asian” encompasses so many different communities, histories, and cultures, as well as specific individual experiences. As a result, art and literature provide a vehicle for giving voice to all of this multiplicity, sometimes massaging it into a rough assemblage but in other cases, highlighting the conflicts and disjuncture.

“Above all, I think art and literature showcase how 'Asian' can be used as a creative and critical tool for encouraging thought and questioning, particularly on different (hopeful) forms of community and connectivity.”

Gu Xiong

Professor in the Department of Art History, Visual Art & Theory

Gu Xiong is a multimedia artist from China who now lives in Canada. He has exhibited his work nationally and internationally in over 100 group exhibitions and more than sixty solo exhibitions, with his works represented in various museums and private collections.

Can you share with us a piece of art or literature that you feel reflects your experience as an Asian person in the UBC community and also celebrates your Asian Heritage? How has this piece impacted you personally or professionally?

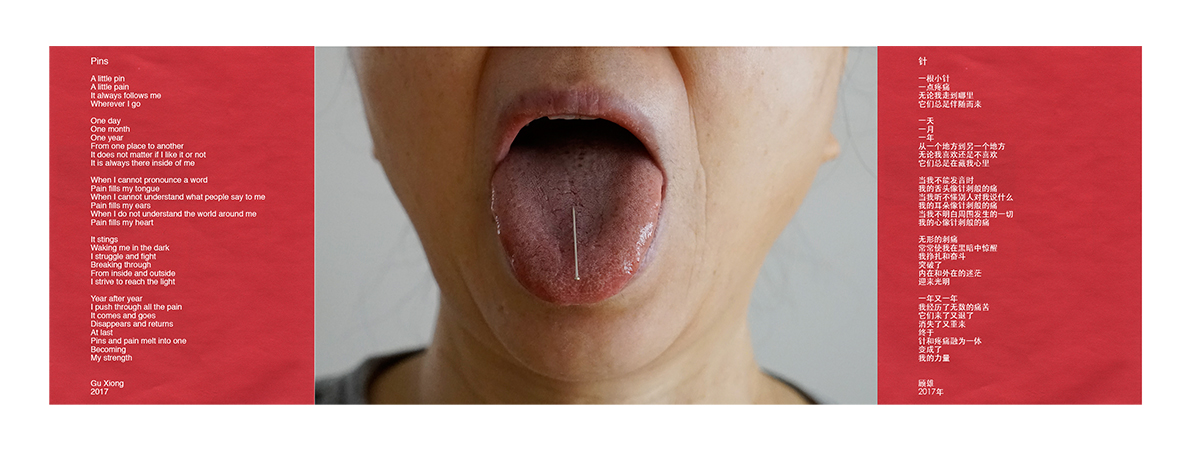

In this Pins photograph, I explored my cross-cultural experience and subtle but unforgettable memories that are hard to articulate through language. Pins serve as a symbol of pain experienced by immigrants in the process of identity transitions that often entail misunderstandings, conflicts and tensions when they encounter cultural differences and language barriers. This pain, embodied by pins, constantly pricks me but never actually causes physical damage. Even though this pain has become bearable as time goes by in my life, it never ceases to be a reminder of courage—I shall persevere against all odds.

In the pin-themed photograph, I have expressed the difficulties of immigrant life through photography. A pin was placed on a tongue to demonstrate resistance to uncomfortable situations. Small as it is, the pin can inflict discomfort that cannot be ignored. This discomfort is comparable to what we experience when learning a new language and trying to pronounce unfamiliar words.

Photo Credit: Art Work: “pins” by Gu Xiong, photograph, 2017

In what ways has your Asian heritage influenced your own artistic creations and/or research? Can you share any specific examples of how this has influenced your work?

Our life experience in Canada is by all means connected with that in China. I often use everyday objects—either brought from China or bought in Canada in my artwork. These objects represented different stages in my life: a teacup passed down from my father, family letters were written when I was apart from my wife and daughter, an English dictionary I used in my early years in Vancouver, a message recorder that helped me stay in touch with my young daughter and a pair of scissors my wife has been using to trim my hair for years. These objects tell our family stories across three generations. One’s body and soul can survive destructive cultural clashes and regenerate life only when we recognize the connection between the old and the new across temporal and spatial boundaries. These ordinary objects are things we have shared with family and friends even today.

“The role of art and literature can lead us through hardships in cultural transformations and guide us in the long course of life. This is how we find where we belong in life.”

Dr. Mila Zuo

Associate Professor in Department of Theatre & Film

Dr. Zuo is a cinema studies scholar whose research areas include transnational Asian cinemas, film-philosophy, and critical theories of gender, sexuality, and race and ethnicity. She is also a filmmaker who writes, directs, and produces narrative films, visual essays, documentaries, and music videos.

Can you share with us a piece of art or literature that you feel reflects your experience as an Asian person in the UBC community and also celebrates your Asian Heritage? How has this piece impacted you personally or professionally?

I’ve recently had the opportunity to lead a conversation at the Contemporary Art Gallery (CAG) around Diane Severin Nguyen’s recent video installation If I hadn’t created my own world, I would have died in someone else’s, a film about a young Chinese actress who is cast in a movie about the Nanjing massacre. Encountering this work has meaningfully contributed to my recent research on trauma, particularly in terms of intergenerational and historical trauma.

Nguyen’s stunning film reveals the ways in which mythologies of trauma haunt generations of people and that the iconicity of trauma remains in our collective consciousness, like a sticky object. I am fascinated by the complex and nuanced ways Nguyen attends to pleasure and desire around trauma, in particular, and I plan to write on Nguyen’s larger body of films for my second book project. This work has also inspired the ways I will be approaching my own forthcoming experimental documentary, Mongoloids, which centers on my family’s experiences during the Cultural Revolution and their subsequent migration to the US. In encountering Nguyen’s work, I recognize the power of contrapuntal audiovisuals: how pairing the soft and hard generates a powerfully complex moment of recognition with a traumatic history.

Photo Credit: Photo from film, If I hadn’t created my own world, I would have died in someone else’s , by Diane Severin Nguyen

In what ways has your Asian heritage influenced your own artistic creations and/or research? Can you share any specific examples of how this has influenced your work?

As a scholar-filmmaker, I am interested in the psychic dimensions of racialization and how desire, disgust, and fear are often entwined in the subject’s attitudes toward racialized gender and sexuality. In my first film, Carnal Orient, I explore the appetite for Asian bodies and food and their conflation. In my award-winning book Vulgar Beauty: Acting Chinese in the Chinese Sensorium, I think about the sensorial ways in which we engage with Chinese femme bodies on screen.

How do you see the role of art and literature in promoting Asian culture and heritage?

I am interested in the ways that art mediates our understanding of “Asian culture and heritage” as dynamic, processual, and political sites of identity and belonging. It’s important to bear in mind that “Asian” as a term arises through geopolitics, and that there is no such thing as an essential Asian identity, culture, or heritage. The moniker “Asian American” arose during the civil rights movement as a way to advocate for the collective rights of a group of otherwise disparate nationalities and peoples, in solidarity with other racialized peoples in the US. Thus, what we think of as “Asian” has always been shaped by politics.

As the Pulitzer Prize-winning Vietnamese American author Viet Thanh Nguyen has recently asked us to consider, there is no reason why we cannot consider Palestine as part of Asia (it is in western Asia), for example. As a scholar whose work necessarily involves thinking about social justice, I am excited by this proposition because I believe that when we use terms like “Asian” to signify, it must be meaningful. Like Viet Thanh Nguyen, I am interested in expansive solidarity, and I look forward to teaching and researching Asian cinemas capaciously, by attending to the beautiful and extraordinary films of Palestinian filmmakers like Elia Suleiman, Jumana Manna, and Michel Khleifi, to name a few.

What challenges have you faced as an Asian researcher? How have you overcome them and what advice would you give to others who may be facing similar challenges?

The challenges I have found as an Asian researcher spring from the fact that many disciplines are still largely anchored in universalist and totalizing approaches that implicitly center on white, western (also ableist and heteronormative*) subjects while pushing questions of difference to the side. As such, Asian topics are often marginalized or seen as less rigorous, exciting, or important.

“There has been and will be growing interest in underrepresented subjects, so my advice for others is to simply persist.”

*Heteronormative: Of, relating to, or based on the attitude that heterosexuality is the only normal and natural expression of sexuality.