Fully searchable banned book database catalogues 125,000 titles

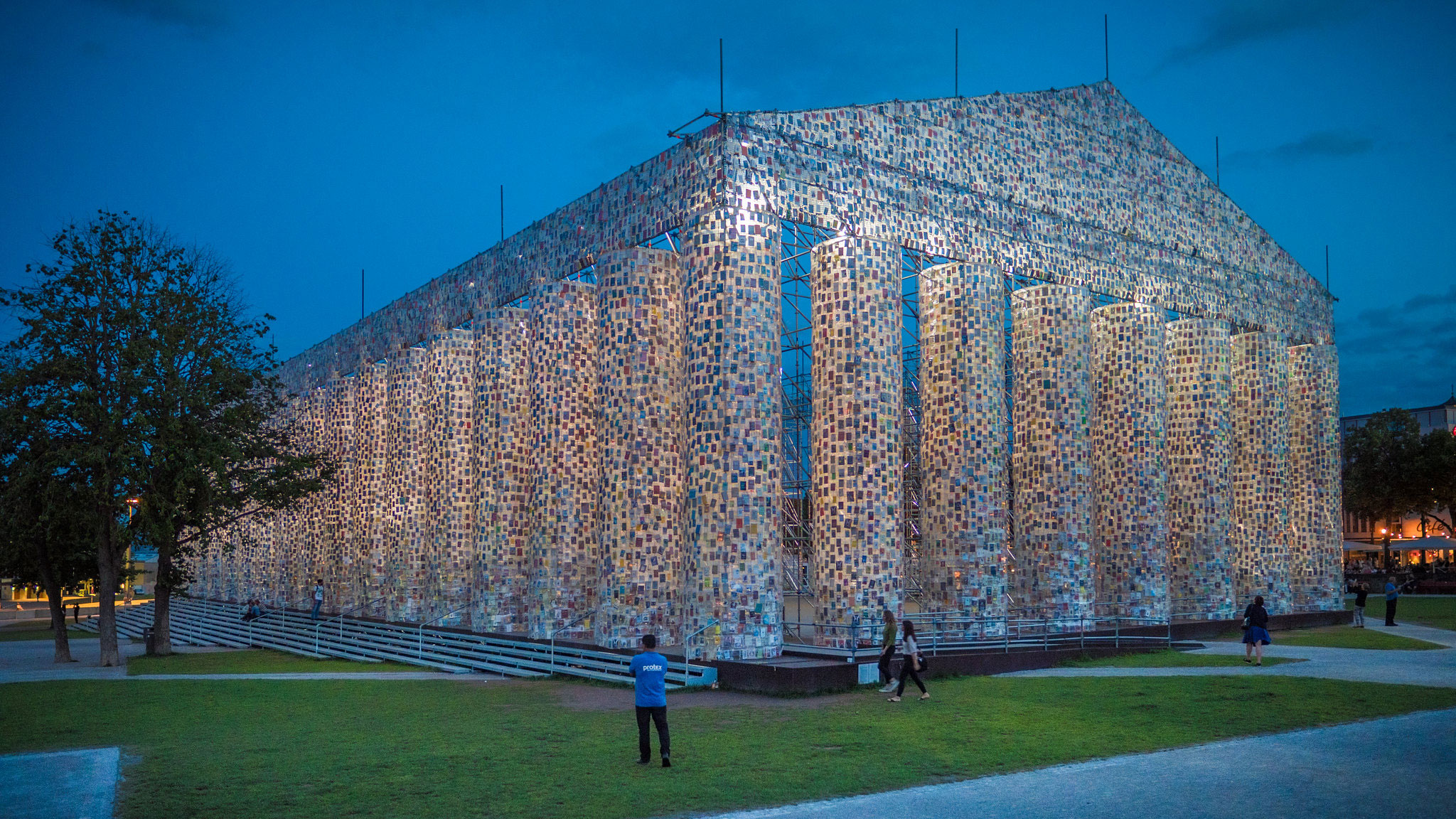

When Argentinian artist Marta Minujin wanted to build a replica of the Parthenon out of banned books, UBC professor Florian Gassner was one of the first people she turned to for help.

Gassner, a senior instructor in UBC’s department of Central, Eastern, and Northern European studies, was a visiting professor at the University of Kassel (Germany) at the time. He and colleague Nikola Roßbach came up with list of 70,000 titles that Minujin used in her work.

But they weren’t done. After The Parthenon of Books was unveiled in 2017, Gassner, Roßbach and a team of students went to work on a new project that launched last month.

We asked Gassner what it’s all about.

Florian Gassner

What is this new resource you’ve created?

It’s an online database, fully searchable, listing—at this point—125,000 books that have been, or currently are, banned or censored somewhere in the world.

That’s a huge number. Is it more than you thought?

Even though 125,000 sounds like a lot, it’s just a fraction of the books that have been censored. The fact that it’s so incomplete is one of the most important messages here, because it not only sheds light on what has been censored, but also that we need to pay more attention to where things are being censored and nobody’s really noticing. The best examples of that are the books of Chinese dissidents these days. The most fascinating books are always the ones that aren’t published, and many of these dissidents only start reaching an audience once they are beyond the borders and confines of their country.

How can people use this database?

They can find the name of the author and title of the book, when it was first published, by whom it was published, and most importantly, the country and year in which the ban was enacted. We provide fairly basic information about these items, but in the final column you can find links to more sources of information about the particulars of the ban. One other feature we’ve built in is that people can actually contribute to the database. When people add something, we get an alert, we validate it and then we add it to the list.

What surprises will people find in there?

Whenever we go through the list, we’re forced to reconsider what we believe censorship to be. For example, Harry Potter was censored. This was because parents wanted Harry Potter to be removed from school libraries in the U.S. On the one hand, we say that’s censorship. On the other hand, parents have a right to decide what children are exposed to.

Or if you look at a book like Hitler’s Mein Kampf, that’s been censored in many countries and contexts. However, it has not been censored in the Federal Republic of Germany after 1948, because in the constitution of Germany—where I’m from—it says censorship does not take place. At the same time, the state government of Bavaria from 1948 to 2015 held the copyright to Mein Kampf through Hitler’s estate and in that time prevented any reprints. So is this censorship or not?

Who do you see using this resource?

Basically three different groups. It could be for anyone who stands in front of their bookshelf and wonders if a particular book ever caused any stir or trouble. For students who work in this field, it will be a starting point to research additional information. And finally for researchers—I myself was recently fixing a couple of lines of code in the database and came across a name I was vaguely familiar with. I started looking into this character, and I have decided I am definitely going down that rabbit hole.

This article was originally published on UBC News.