How do Black students, faculty and staff deal with racism on campus in the age of #BlackLivesMatter? How do their university environments affect them in their struggles against injustice? How do Black people make meaning in an anti-Black world?

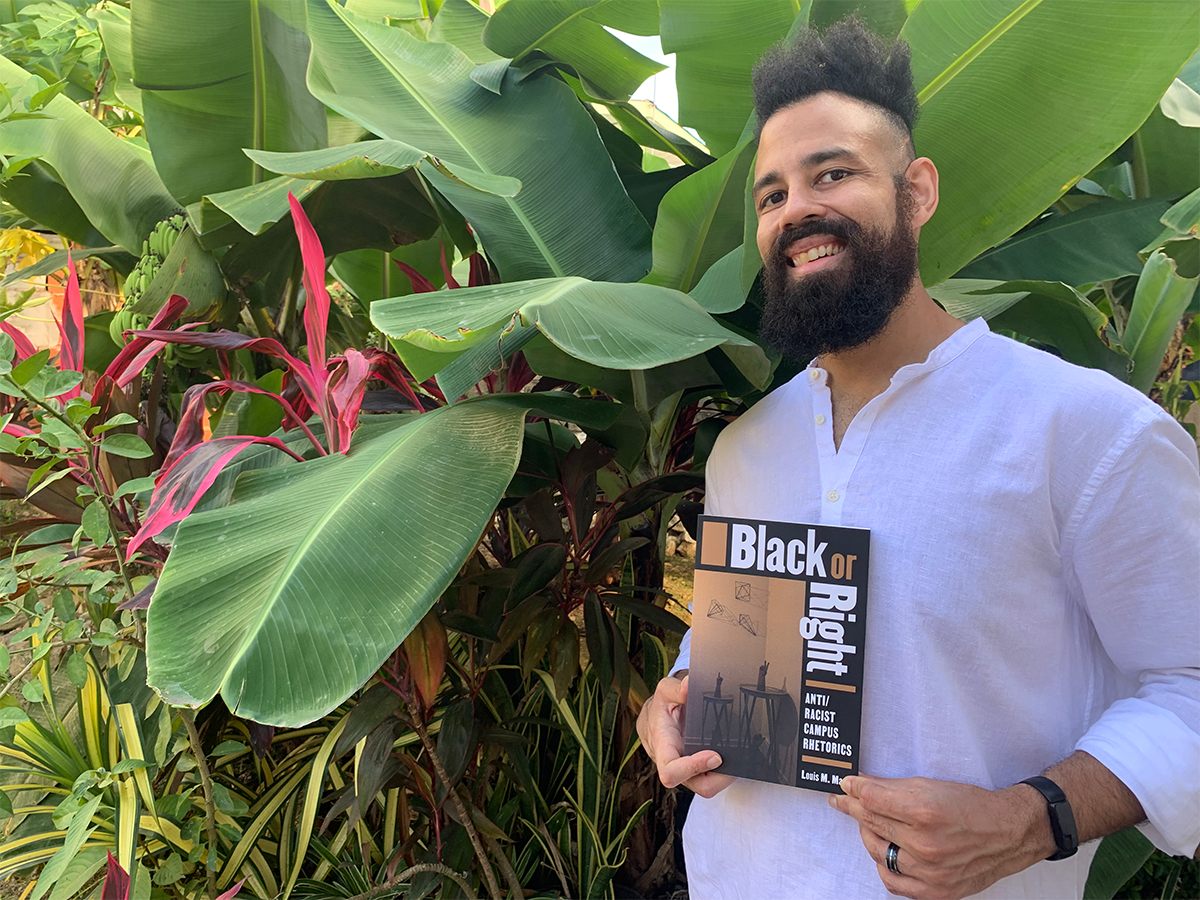

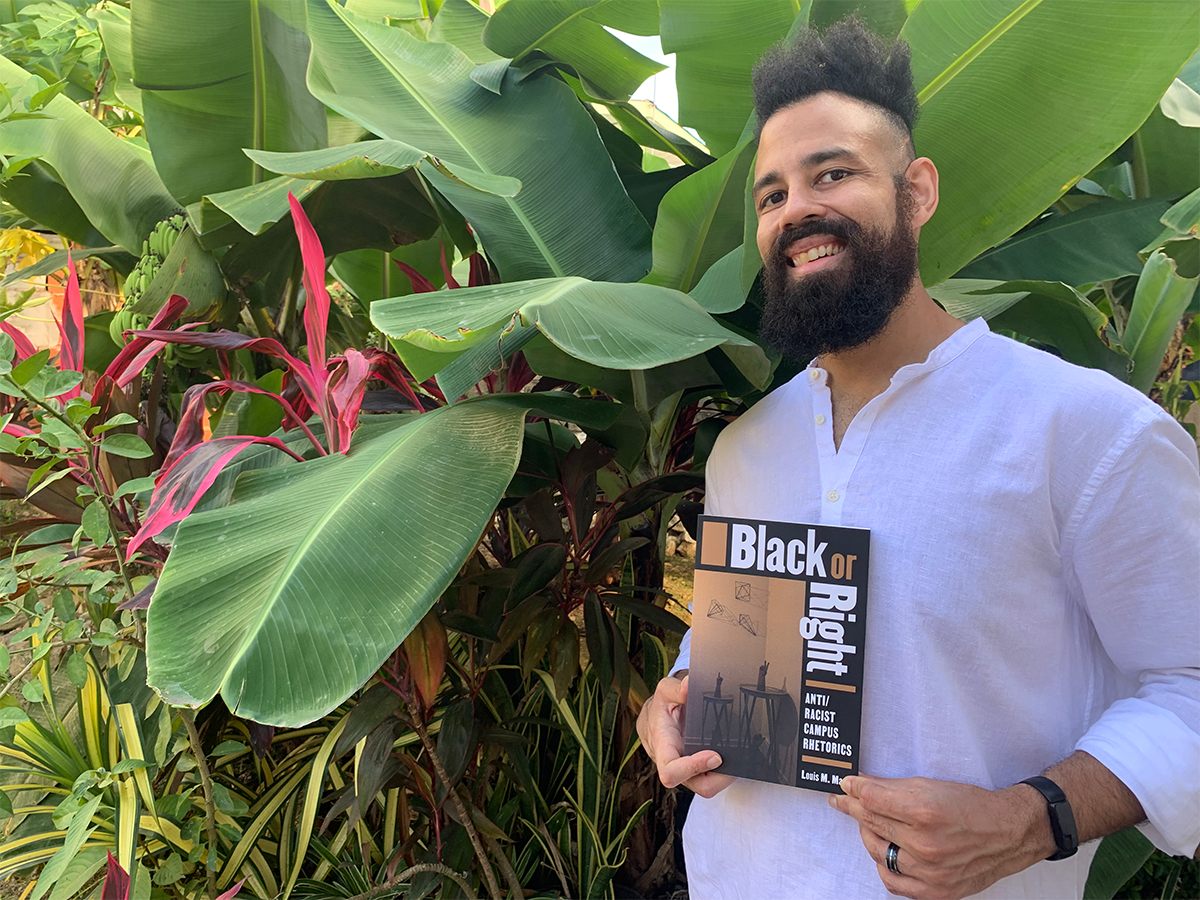

These are some of the questions that Louis Maraj, a new professor in the School of Journalism, Writing and Media, explores in his latest book, Black or Right: Anti/Racist Campus Rhetorics. He recently received the 2022 Outstanding Book Award from the Conference on College Composition and Communication. We spoke to him about the key ideas in his new book and why he wrote it.

What is your book about?

Black or Right explores notions of Blackness that circulate in and beyond historically white university spaces. It looks at how Black students, faculty, and staff navigate these ideas about them[selves] and their cultures, while also paying attention to the ways that the #BlackLivesMatter movement has impacted those ideas. Each chapter offers a particular meaning-making tactic that Black folx use to resist the antiBlack racism that they constantly face on white campuses. These strategies are Black auto-ethnography, Black hashtagging, Black inter(con)textual reading, and reconceived Black disruption.

I tell stories about having my racial identity questioned, about how my own image was used to promote institutional “diversity,” and about violent encounters with police and vigilantes in university-adjacent communities. I also think through the racial politics of how Black students, staff, and faculty engage university policies and moments when they are deemed as violating them or “deviant.”

Ultimately, Black or Right demonstrates how racism and anti-racism play out in white university spaces where Black peoples are often regarded as markers of “diversity,” while routinely criminalized, stereotyped, tokenized, hyper-sexualized, and brutalized. It asks us to move beyond reactive anti-racism that puts changing white people’s minds and institutions at the center of what antiracism does. At the same time, the book highlights the important ways Black people must continually invent means of escaping anti-Black violence in knowledge-making systems and spaces.

Why did you write this book and why is this subject important to you?

In some ways, this book wrote me. My entire life in the Global North—first as an international student, then as a migrant worker—has been spent in and around educational institutions, particularly universities. My experiences inside and outside of classrooms taught me about the workings of race, gender, class, dis/ability, nationality, language etc. Specifically, though, the idea for Black or Right was catalyzed by an incident I describe in the first chapter of the book. While teaching as a graduate instructor, a Black male student in one of my classes kept interrupting class to ask me “are you Black though?” even though I’d constantly answered “yes.” With that question he once asked if he was a field slave and I a house slave. It was clear to me that where we were, how we were positioned, and how power was working in that space had caused what some might see as a classroom “disruption.”

It was in sitting with that disruption—this question of “what is Blackness?” which then evolved to “how do environments affect what and how Blackness might mean?”—that led me to my research on how Black people communicate and how their environments affect them in struggles against injustice.

What is “rhetorical reclamation” and what are some examples of this?

Rhetorical reclamation is a key concept in Black or Right that brings together four meaning-making strategies I mentioned previously (Black auto-ethnography, hashtagging, inter(con)textual reading, and generative disruption). These rhetorics are most visible in moments of racial stress: incidents where an act of racism does violence to Black and other marginalized peoples. Under this stigmatizing white gaze, these folx might turn such moments on themselves to assert agency through rhetorical reclamations. For instance, hashtags that emerged through the Black Lives Matter movement like #IfTheyGunnedMeDown laid bare the ways that the media often casts Black people as criminals when they become unfortunate victims of police and vigilante violence. The tag and its posts explicitly racialized racist media representations and their anti-Black politics. Other tags following the pattern #X-WhileBlack reveal the ways Black peoples are criminalized for everyday acts.

Rhetorical reclamations span a range of communicative actions, from rhetorical silence to technologies of “canceling” we might see on- or off- line. Silence, for example, could be used as an effective tactic if you found yourself as the only Black student in a particular class or are chosen as a “diversity” token on a university service committee as faculty or staff. Often, in moments of racial stress, that Black person is expected to speak on behalf of an entire race, region, or even all non-white peoples. By saying nothing, they might reclaim the moment through refusing to be used as an object for soothing the discomfort of the situation. It is important to note that this tactic isn’t simply about turning something perceived as “negative” into a “positive,” as in usual definitions of “reclaim.” Instead, its subversive energy lies in forcing us to consistently question how racialization works: understanding “re” as turning once more and “claim” as a demanding question. So, to “rhetorically reclaim” suggests turning once more to the idea of race to ask: “How is race being made or unmade in this situation?” That constant question works to destabilize racializing tropes that continue to be the basis for racist thought and action.