When examining the politics of Black women, it’s essential to consider their resistance against the various systems of oppression. We had the privilege to interview Dr. Alexis McGee to enhance our understanding of Black women’s ongoing resistance across different media and the support UBC community can provide to this effort.

As the Faculty of Arts reflects on Black History Month, it is essential to acknowledge and celebrate the evolution of Black women’s voices and their remarkable progress in combating oppression.

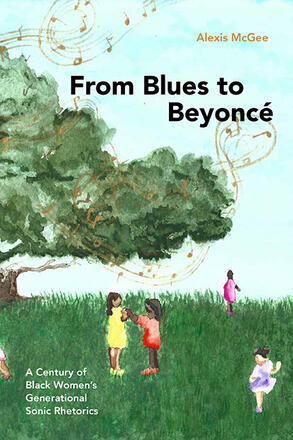

Dr. McGee is an Assistant Professor in the School of Journalism, Writing, and Media, who has recently published her monograph, titled From Blues to Beyoncé: A Century of Black Women’s Generational Sonic Rhetorics. She is an expert in various fields and sub-disciplines such as Rhetoric, Composition/Writing Studies, Black Studies, Critical Pedagogies, Sound Studies, as well as Women and Gender Studies, and primarily focuses on Black women’s rhetorical use of voice, literacies, and expression.

“UBC can learn a lot from Black women, perhaps more specifically from Black feminism. One underlying aim of Black feminism is liberation for all; for that to happen, we have to learn from and sit with differences in order to make headway with our social justice efforts.”

*This editorial was revisited in August 2024 in light of United States Vice President Kamala Harris using Beyoncé’s song “Freedom” in her presidential election campaign. Dr. McGee has shared her insights.

Dr. Alexis McGee

Assistant Professor at School of Journalism, Writing, and Media

Dr. McGee is an interdisciplinary scholar who engages with various fields and sub-disciplines.

When asked what UBC can learn as a community from the ongoing resistance of Black women in different fields and how we can support their efforts toward social justice, Dr. McGee suggests that building something worthwhile can be challenging and takes time. It may require trial and error, resources, patience, or even silence to gather thoughts. Most importantly, efforts should also not be held back by policies and traditions that create boundaries.

She remarks that the competition encouraged and developed by many initiatives often drives the tokenism that scholars are tired of having to call out. This is akin to much of the work they do; that emotional and physical labour of using voices is limited in recognition and that desire to hold onto exclusionary and elitist forms of “excellence” validates the interchangeability of Blackness.

Dr. McGee’s new book delves into the ongoing public assertions of resistance, agency, and hope by Black women across various media, ranging from the nineteenth century to present day. We spoke with her to learn about the inspirations and takeaways from her new monograph.

What or who inspired you to write your book, From Blues to Beyoncé: A Century of Black Women’s Generational Sonic Rhetorics?

I mentioned in my book that this project was my way of seeing myself because I needed to make sense of the world and how I’ve been positioned within it. All the explicit violence and divisive rhetoric seen in the media, the waves of microaggressions and snarky racist and sexist quips or gestures in my interactions with others, the intimate, gnawing feeling of something missing on both a personal and communal level, needed to be tended. Giving myself the space to sit with those bodily responses gave me time to reflect on all who are a part of me.

From Blues to Beyoncé: A Century of Black Women’s Generational Sonic Rhetorics is inspired by the overwhelming accounts of Black women who are often not credited or heard but still go on maneuvering daily life—with or without recognition. It’s inspired by the countless Black women who have had their stories and struggles pushed aside and discounted, by the everyday attempts to survive in an anti-Black world. It’s not just about individual figures (like Toni Morrison; Lauryn Hill; Nina Simone; Megan Thee Stallion; Ida B. Wells; etc. that I mention in the book) that serve as the foundation to this work, but it is also about the everyday examples of creative ingenuity ordinary Black women exude when we move forward in the world. In my opinion, that is not showcased enough; I wanted to celebrate that and celebrate us.

“With that, I wanted to celebrate, honour, and respect the daily lives of Black women. This work was inspired by my overwhelming adoration and love for Black women and my urge to celebrate the abundantly clear (to me) ways in which we, time and time again, make a way out of no way.”

In what ways have Black women used their voices as a form of resistance against oppression?

Because this project is bound by the genre and page limit, as well as by the fact that Blackness is not monolithic, I couldn’t explore the myriad of methods used by Black women who mobilize voices as resistance. However, I was able to deeply engage with a few methods I (and other scholars) have noticed: song, visual arts, dance, journalism, mentorship, and life writing to name a few. While these methods may not explicitly speak to “voice” in a traditional sense, all of these pathways resonate with a sense of agency, subjectivity, experience, and situated context which are all aspects of “voice” as a rhetorical discourse.

Can you discuss some of the challenges Black women have faced in their efforts to make their voices heard and recognized?

One of the biggest challenges to being recognized is that the very framework of our societies is racist, sexist, classist, ableist, ageist, and xenophobic. The climate we live in, particularly societies developed from colonial practices, are conditioned to disregard and pilfer from Black women (among others). And, the generations of attempts to silence, ignore, marginalize, and erase our voices is a constant reminder of all the work still left to do. It is exhausting and sometimes distracting from the work we might want to do. Having to chip away at inequity constantly has sent many activists and educators to early graves, be that from sanctioned institutional violence or from exhaustion.

In your opinion, what role do Black women play in shaping our understanding of Black history

We have everything to do with shaping our understanding of history. You can’t ignore whole lineages, contributions, and ways of thinking that Black women have offered the world despite the ways our contributions have been minimized, erased, and/or co-opted. If we don’t acknowledge Black women’s contributions to how the world has been shaped over time, then we would be at a great loss for understanding how to be in the world. From Blues to Beyoncé is one way of helping others see what they miss when they accept dominant histories as truth–histories that often render Black women’s importance as at best contingent and at worst invisible.

“I hope, at the very least, UBC communities can learn two things. First, that Blackness is not monolithic. We all might not have the same end goals or method(ologies). We aren’t all best friends, but it doesn’t mean we can’t work on similar things; it doesn’t mean that we can’t build multiple routes simultaneously to a shared dream. Second, that we aren’t interchangeable parts, so institutions should stop treating us as such.”

How did you react to Kamala Harris using Beyoncé’s song “Freedom” in her presidential election campaign? What message do you think Kamala Harris intended to convey by choosing this particular song?

Political anthems and themes songs, play a crucial role in setting the mood for campaigns. I was moved when I saw Vice President Harris use Beyoncé’s “Freedom” for her presidential ad. While not all of Harris’ ads incorporate the song, her use of the tune has sent a powerful message to voters and those watching this race unfold.

Harris’ choice in introductory music reinforces the long standing, powerful ties between music, politics, and culture. Some political correspondents have even likened the choice and the energy surrounding Harris’ campaign to the 2008 election, where hip hop and Black culture were central in mobilizing votes.

The use of Beyoncé, a Black woman from the American South, and Kendrick Lamar, a Black man from her home state of California, as the backdrop for her political campaign sends the message that Harris understands the richness and diversity of Blackness in the United States and has not lost sight of her culture and heritage as she navigated the political landscape. Using this song from a relatively recent and award-winning album also signals that she is in touch with younger voters who often re-energize political movements.

Harris’ choice in incorporating Beyoncé’s song is tremendously significant as it sends a strong message of a particular kind of freedom—one that has been long in the making and one that amplifies the collaborative and intergenerational work of Black women who call for freedom, justice, and equity across all planes. Within this larger context, Beyoncé’s song exudes strength, determination, frustration, and hope—all characteristics I think Harris wants to convey to voters.

This song and the artists highlight the important work of Black individuals who have dedicated their lives to community organizing and the pursuit of freedom for all. The song also acknowledges the significant personal cost of this freedom work, including experiencing terror, gaslighting, premature death due to stress or other factors, the loss of family and friends, and being made hypervisible and interchangeable at the same time.

“Most importantly, mobilizing this song for her candidacy also signals hope on the horizon: a message that our frustrations and sacrifices have not gone to waste or our calls have not been unheard. This is a particular kind of hope, a hope that remembers why we continue to push for freedom and why we hold on to emotions that drive us forward. That, I think, is a powerful message to make as a cornerstone of her campaign.”

From Blues to Beyoncé: A Century of Black Women’s Generational Sonic Rhetorics

Dr. Alexis McGee’s new book explores how Black women continually use sound to convey stories and forge community across generations.

Learn more