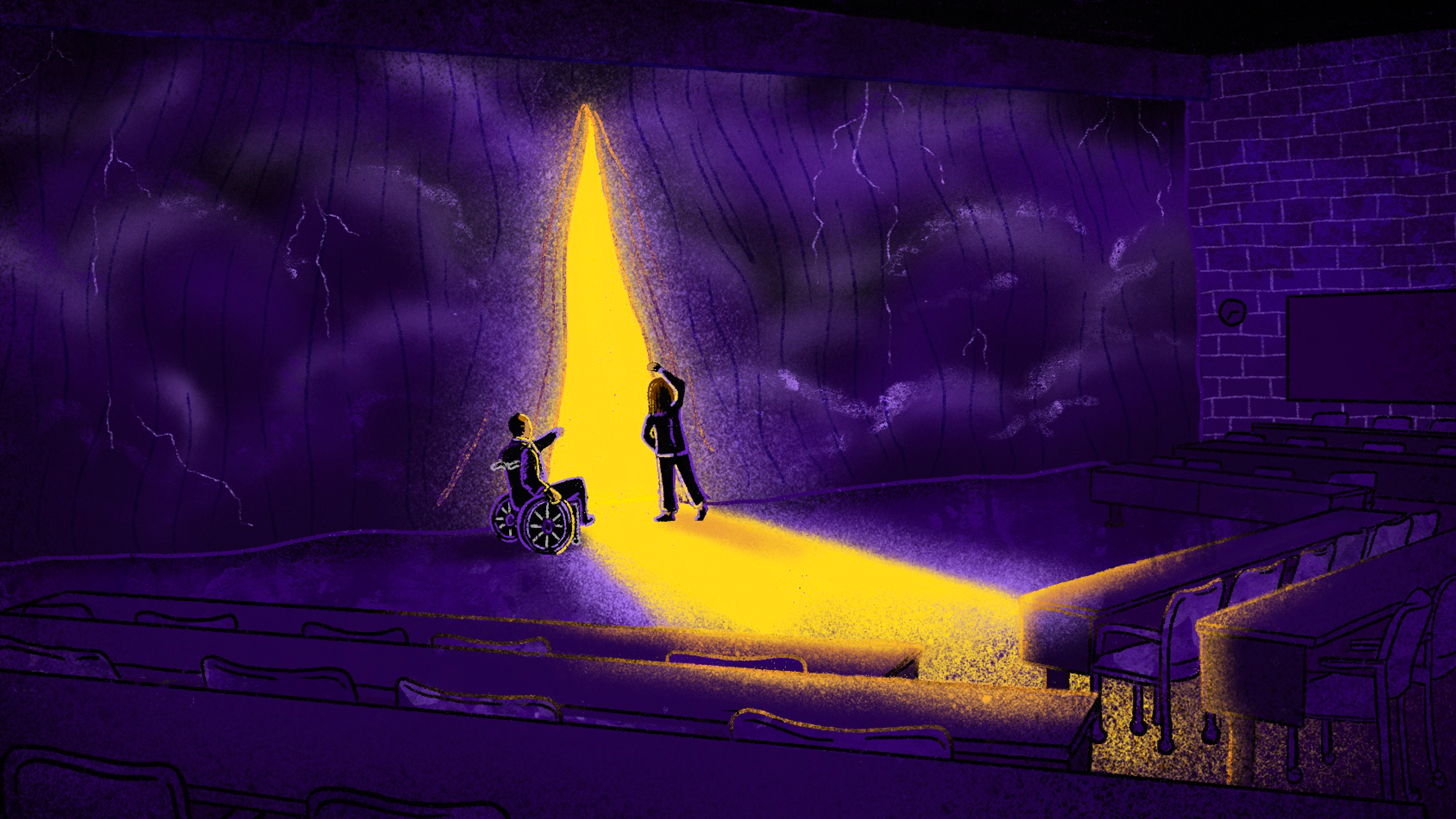

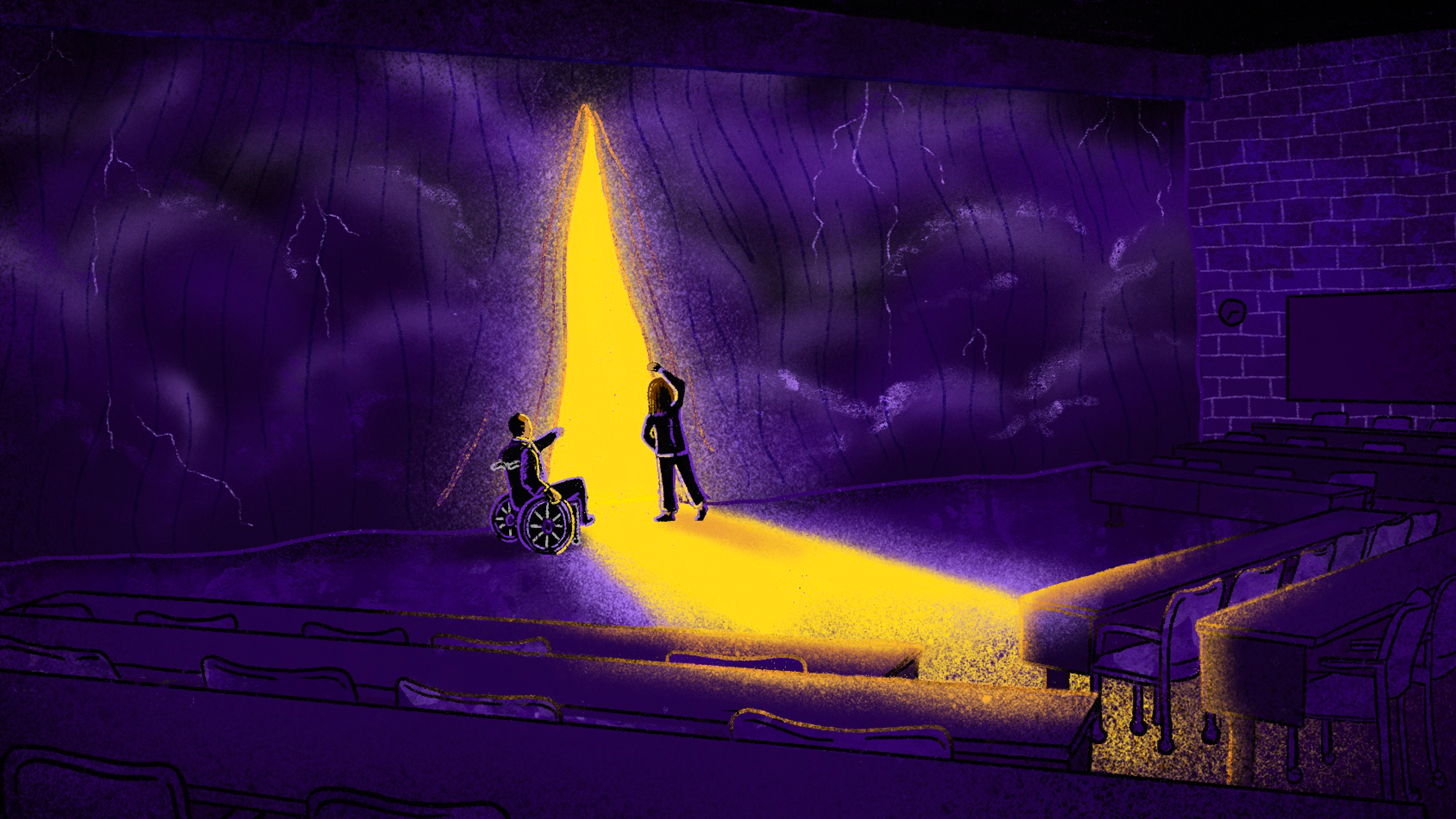

When Olivia Dreisinger started her podcast, Diagnosis Grad School, she wanted to take people on a multifaceted journey through the lens of a disabled graduate scholar. Upon its completion in April, she has created her own variety show that unmasks the challenges of ableism in higher education.

Dreisinger, who is a PhD candidate in the Department of English Language & Literatures, is committed to raising awareness about the barriers faced by individuals with disabilities in post-secondary institutions. Whether it’s in the Humanities, Sciences, or other disciplines, requirements that are deemed “normal” in academic settings can enforce ableist conditions that fail to take into consideration the nuances in a disabled person’s experience. Dreisinger explains: “A participant I interviewed was in sciences and a lot of it is lab and field work research so you need to be physically able in a particular type of way. If you’re not, that puts you at a disadvantage.”

Becoming disabled during her Master’s, she felt that she was failing by the university’s standards of engagement: attendance. Reflecting back on the pandemic, Dreisinger appreciated the temporary flexibility and accommodations—studying from home, extensions, empathy—before it was all taken away. “Even non-disabled students might have family or personal things that impact their time or finances towards their degree. So why does university have to be like this?” she emphasizes.

“Think of other ways of doing things in the university. It can really benefit particular people doing research in the university and also outside in the broader community. Instead of being insular research, it can reach and impact non academics too.”

More often than not, the expected output from a graduate student is a final paper. But why is that? In resistance to accepting the existing standards, Dreisinger created a riveting and intimate podcast that tells the story of her disabled friends while integrating parallels with iconic references like Phantom of the Opera, Mary Shelley, Victor Frankenstein, and Octavia E. Butler’s parable series. While big media regurgitates narratives (written by non-disabled people) about disability, Dreisinger paints a picture of reality “being in the disability community, talking to my disabled friends, we know what a disabled life is. It’s full of joy, other experiences, and barriers…Disabled people are normal people doing normal things. Please don’t make us inspirational.”

We spoke with Dreisinger about the realities of ableism in higher education and how universities can better support disabled scholars throughout their academic journey.

While accessibility in academia can look drastically different for various peoples’ needs, what are some changes you’d make to existing practices to reduce barriers?

First, rethinking students needing to have a documented diagnosis to get into the Center for Accessibility and to have this right to be granted reasonable accommodation; because there’s so many barriers to just getting a diagnosis. It takes a lot of time and doctors especially if you’re an international student, you don’t have access to proper health care or time, or become disabled away from home like me. The expectation that you have a documented diagnosis is for people to come into university already disabled. Not considering that a person could become disabled during their educational career. I think that is something that needs to be addressed.

Second, for curriculum environments, one of the people I interviewed, Emily Sara, talks about her class where sometimes the students can opt out of assignments if they need to. And I thought that was radical. It blew my mind for a professor to say, “let’s talk and think about something else that you can do, to show that you’re engaged, learning, and developing in a scholarly academic way.” I’ll have to say that as an addendum, that requires a professor to have job security, to be paid fairly, to have time to be supported by the university in order to offer this kind of tailored support to students.

Lastly, in terms of academic standards, rethinking mandatory attendance in certain departments because that’s not a thing that exists in all departments. Rethinking grading systems as well. I talked to a professor the other day who hates grades and wants to assess student learning in different ways that aren’t grades-based. There are lots of professors who are thinking about that. These are such big things so how do you change the entire university? Not one single person can do that alone.

Diagnosis Grad School podcast artwork created by Audrey Leshay.

What is your baseline of feeling reasonably accommodated?

I have that now because I have a good supervisor who is also disabled so they get it. In the final podcast episode, I asked people for advice and one of them said to have a great supervisor who understands. And I agree with that. They’re well positioned to advocate for you to have that flexibility to some degree. That’s what I would want for everyone — to be able to have more time if they need it.

The UBC Public Humanities Hub and the Public Scholars Initiative are great too because they’re really trying to rethink modes of research that are not just scholarly articles. Like documentaries, Wikipedia edit-a-thons, you know, what can scholarly research look like? I’m thankful that they think podcasting is good research. Dr. Mary Chapman started me on that track. She was my professor in undergrad and grad school. She introduced me to Anna Williams’ My Gothic Dissertation, and in her class one of the things you could do is make a zine, podcast, or other than paper.

“Nurture what you love doing. The best, most authentic work that you can produce is something from your heart.”

What are you excited about?

I’ve been working on a documentary that got funding from Canada Council of the Arts, BC Arts Council, and recently, the National Film Board of Canada. I feel very happy about that. So the documentary will be done in the Fall. It was one of my dreams so I feel very thankful to have achieved that.

It will be about my mother who passed away in 2012 and sort of about her illness and my illness, and then me thinking about becoming a mother and what kind of mother I’ll be. It’s called “What Kind of Mother.”

What advice would you give to disabled scholars?

You’re valuable as a scholar. Please don’t feel bad about yourself. There are so many amazing disabled scholars I know and they blow me away with their ideas and brilliance, and how they tried to stay in institutions that don’t really want them. Your views and what you bring to academia and research are going to be valuable.