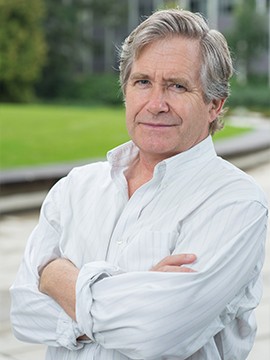

By Nick Melling

When Professor Steven Taubeneck walked into the classroom for the first time as a teacher, he says the class just laughed.

Freshly arrived from the free-wheeling UC Santa Cruz of the 1970s, with hair past his shoulders and a deep tan, the 28-year-old budding academic seemed an unlikely candidate to teach the language of Goethe and the philosophy of Kant. “They took one look at me and thought ‘we can handle this guy,’” Taubeneck recounts. “I laughed right along with them.”

And his rapport with his students remains just as strong today. Guided by the deceptively simple principle that “undergraduates should not be tortured,” he was awarded a Killam Teaching Prize in 1995, the very first year he was eligible.

But this acclaimed teacher didn’t always see teaching as his lot in life. “My first ambition was to be a priest,” he explains. “Then I found about sex, so I decided I couldn’t do that. My next ambition was to be a doctor. Then I found out about surgery, and I knew I couldn’t do that.”

What followed next was an 11-year undergraduate odyssey that took him through nine different universities and six different majors, from concert piano to creative writing to Irish history. In the end, he settled on German language and literature, which he teaches today out of the Dept. of Central, Eastern, and Northern European Studies.

Taubeneck admits that it’s a discipline that might seem irrelevant and removed from life in Canada. But he thinks the issues that German thinkers have long struggled with — the nature of authority, for instance, or how to deal with the past — can be applied to anyone, anywhere. “In some ways, the Germans are ‘extremely typical,’” he explains. “German history exhibits many of the same tendencies as the histories of other nations.

“At the same time, there is something both horribly monstrous — Hitler — and very attractive — Bach, Mozart — about German history,” he adds. That’s why the reading lists in Taubeneck’s classes include not only literary and philosophical classics, but also such infamous books as Hitler’s Mein Kampf. “It’s important to read Mein Kampf in order to begin to understand the rhetoric Hitler used to attract his followers,” Taubeneck explains. “If we can read Hitler and recognize a certain familiarity to our own times, we can better avoid similar demagogues.”

Even his own life, Taubeneck feels, can be seen through the lens of German literature. He says he identifies with Gregor Samsa, the main character of Franz Kafka’s Metamorphosis, who turns into a giant insect and is rejected by his family. Born into a family whose main interests lay in the business world, Taubeneck has never felt that his parents were comfortable with career choice. When he began reading Kafka and Nietzsche at age 11, they viewed his interest in German culture as an oddity at best, and a symptom of proto-fascism at worst.

But Taubeneck, who says that he went into German literature partly to fight against absolutist ideas, was unperturbed. In his view, the passion for one’s field of study is exactly what makes a good teacher.

“Professors are really just older children who have followed their obsessions to the point of making careers out of them,” he observes. “Aren’t they?”

Students who share Taubeneck’s obsessions can join him in one of five upper-level classes. Topics range from wartime literature and European politics to communism and existentialism.