“Symbols for Education” mural on the purpose-built wall outside Brock Commons South. Photo: Michael R. Barrick

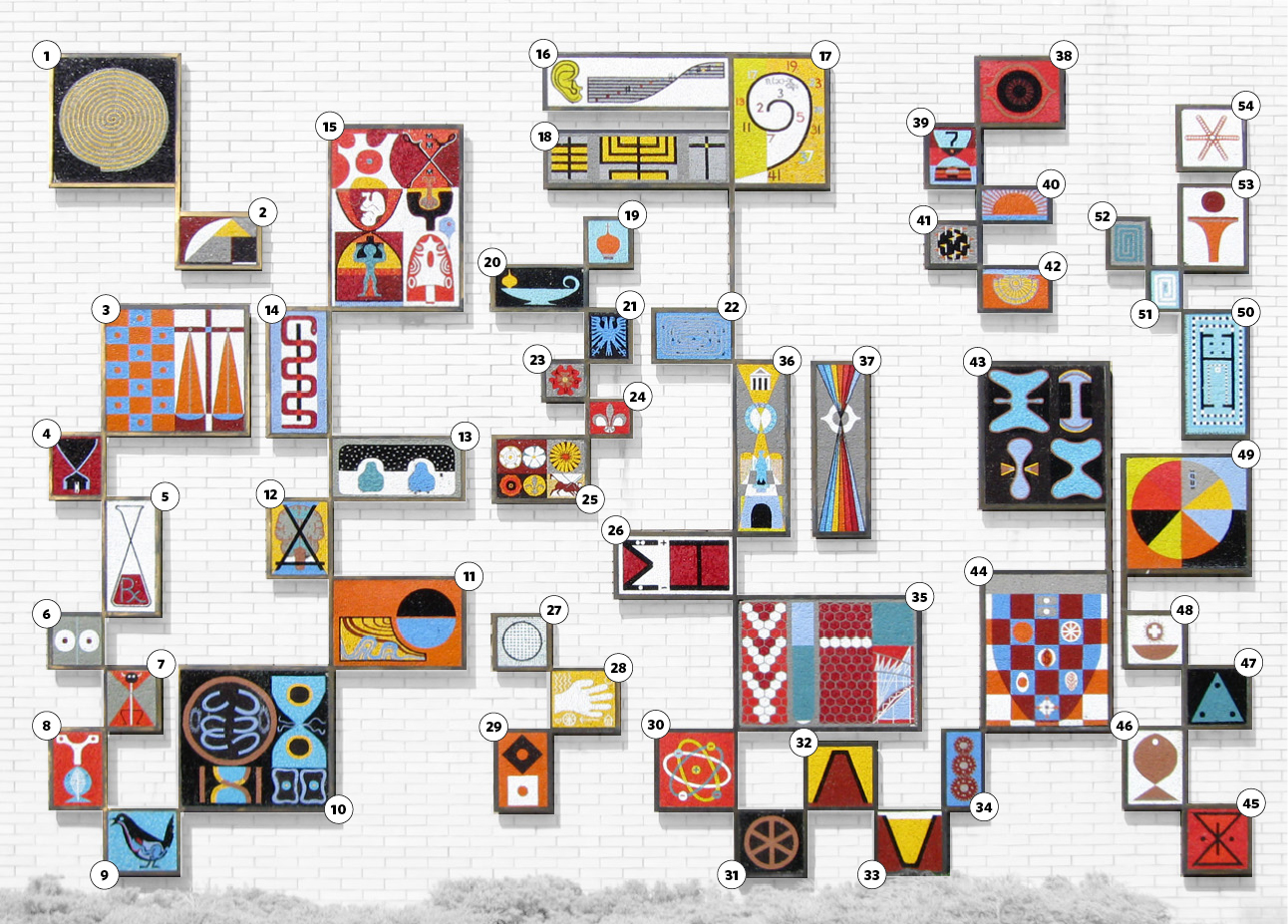

What happens to outdoor artwork when time has run its course? Symbols for Education by Lionel and Patricia Thomas illustrates the different faculties and departments at UBC during the end of the 1950s. Commissioned from the graduating class of 1958, the mural embodies a time capsule that reflects the interwoven relations across campus.

“On campus, people routinely walk around, eat lunch at, and read underneath public artwork, and so I think it is weighty indeed as an expression of those very social relations.”

This legacy artwork is depicted in glass mosaic (tesserae) inspired by modernist architecture and was hosted near Brock Hall, the former student union building. With its new home on a standalone wall in Brock Commons, it was vital for Barbara Cole, former project lead and outdoor curator of Belkin, and Fraser Spafford Ricci Art & Archival Conservation Inc. to enhance the artwork for longevity while staying true to its original purpose. “We always ‘listen to the object’ and let it guide us in our decisions. Conservators’ ultimate responsibility is to the artwork and the original artists; improvements can be made within the work and behind to ensure preservation and stability, but the appearance and originality must be maintained as much as possible…with the artist’s intent as the strongest voice,” says Sarah Spafford Ricci, Principal Conservator.

The Belkin Art Gallery plays a vital role in promoting dialogue and research around the outdoor artwork on campus and within their collections. The Belkin’s outdoor artwork reflects the multiple voices and stories that not only relate to its history at UBC but act as a reminder of the ongoing conversations that need to be had about place. “Art — especially outdoor art — is a site of shifting narrative about space and place, place-making, and the history of the traditional, ancestral, and unceded Musqueam territories on which UBC resides,” says Melanie O’Brian, Associate Director/Curator for Belkin Art Gallery. “From Brent Sparrow’s Musqueam post and James Hart’s Reconciliation Pole (with Musqueam artist Richard Campbell bronze disc base) to Edgar Heap of Birds’ Native Hosts signs, these works tell complex stories and ask viewers and visitors to process their own positionality on these lands and in relation to these works.”

“Public art reflects conditions of its time while marking a moment within an evolving context.”

To get a better sense of the important symbolisms and nuanced considerations of the reinstallation, we received insights from key contributors and current members of the Arts community to weigh in.

What were the considerations in maintaining the mural’s original story and significance while integrating it into a new environment?

Barbara: When the Belkin Art Gallery was alerted to plans for decommissioning the Brock Hall Annex to make way for the new and expansive Brock Commons, the first round of questions brought forward to the University Art Committee centered around the artwork’s place within the larger Outdoor Art collection. What did it represent in relation to the history of art in public space? Was it inextricably tied to its site? Could it be moved and still retain its relevance? As we worked through the issues and implications of each of these questions, a commitment to preserving the work led to the series of decisions that followed.

The Belkin Art Gallery team explored possible re-locations for the artwork in different areas of campus. The criteria they worked with brought forward important aspects of the mural’s legacy including concerns for context, sight lines, physical relationship to viewers, and integration into architectural space. As part of the planning process and in consultation with the many designers at the table, it was decided that the best course of action would be to design a space specifically for the artwork and in relation to the activities and programming of the new Brock Commons. A purpose-built wall was designed to support the artwork and as it underwent extensive restoration, the engineering and construction of the wall took place on site.

To gain a better understanding of what was required for the Thomas mural’s restoration, we received insights from Fraser Spafford Ricci Art & Archival Conservation Inc. about their process of removing and conserving the legacy artwork.

In 2018 when the wall sculpture was designated for removal from the Brock Hall terrace wall, the artwork was in poor condition with significant degradation and loss of grout and glass tesserae (tiles), cracks and breaks in the concrete, dirt, grime, and biological growth, damage and corrosion on the bronze framing and significant rust from corrosion of the iron components behind the mosaics.

Conservation of the artwork involved the following general steps carried out primarily by lab conservators Tara Fraser, Sarah Spafford-Ricci, Daniel Schwartz and Robin Langmuir:

-

- The conservators initially planned to save and conserve all original material, but the metal framing was too damaged to save, so all metal parts were removed including the bronze frames and the rusting iron framework behind each mosaic, stripping the mosaics down to panels of tiles on mortar on concrete.

- The panels were thinned at the reverse to remove excess concrete.

- Mosaics were deep cleaned at the front and the reverse to remove old grout, biological growth, and years of dirt and grime from the mosaics.

- Breaks and cracks in the mosaic panels were consolidated and repaired using resins introduced into crevices and breaks.

- The concrete bed for the tesserae was rebuilt where it was damaged or deteriorated, and the loose tesserae were re-secured with mortar. Each detached and recovered tesserae was cleaned individually by hand prior to being re-secured.

- The many locations of missing tesserae were matched and positioned with new “smalti” tesserae (an opaque Byzantine glass mosaic tile) and mortared in place to recreate the missing designs.

- The mosaics received fresh grout, and the mosaics and grout were sealed for protection.

- New bronze frames and connectors were fabricated, integrating a concrete support tray and an installation system.

- The mosaics are in the process of mounting into new frames using concrete, as the mosaics were originally mounted.

The bronze frame and metal support system behind the mosaics were refabricated by Perry Smith and Brad Weldon of Accurate Mechanical Systems (AMS) of Delta BC, who worked with Fraser Spafford Ricci conservators to design and construct a strong metal frame and support system. AMS is also securely installing the artwork onto the new Brock Commons wall.

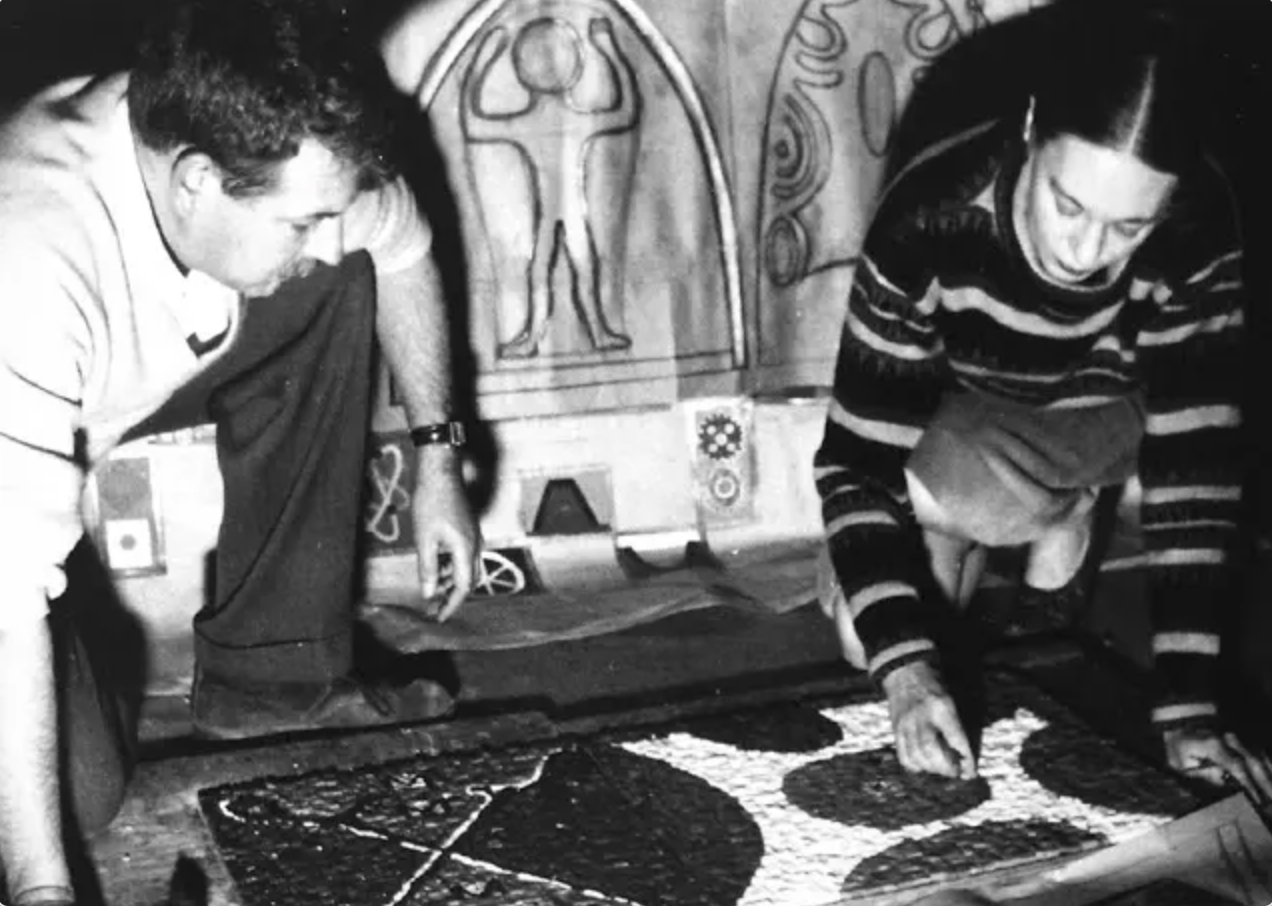

Lionel and Patricia Thomas laying out the tesserae (glass tiles) for the Medicine mosaic panel, ca 1958.

Photographer unknown.

The 1958 “Symbols for Education” was installed by the artists on the wall of the old Brock Hall Annex.

Photo: Howard Ursuliak

The mosaics laid out on the floor inside Brock Hall Annex after it was de-installed.

The damaged bronze frame and corroded iron supporting structure at the back of the mosaics are stripped away.

Credit: Fraser Spafford Ricci Art & Archival Conservation Inc.

The conservator uses a tool to remove grime and deteriorated grout.

Credit: Fraser Spafford Ricci Art & Archival Conservation Inc.

Detached tesserae (tiles) are cleaned individually by conservators to remove dirt, grime and biological growth.

Credit: Fraser Spafford Ricci Art & Archival Conservation Inc.

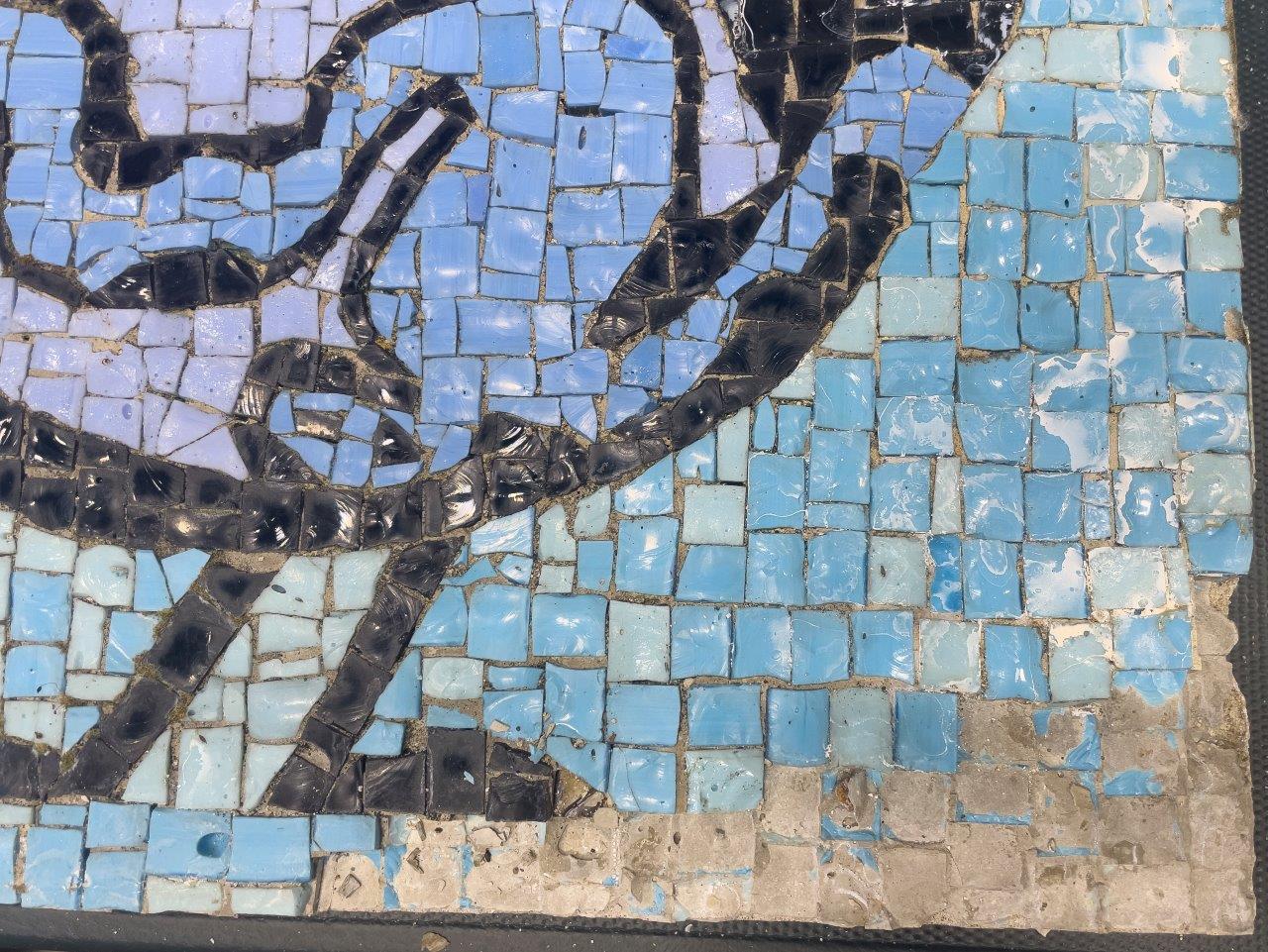

A conservator replaces new and dislocated glass tesserae into fresh mortar.

Credit: Fraser Spafford Ricci Art & Archival Conservation Inc.

The mosaics are provided with new mortar and are re-grouted by conservators.

Credit: Fraser Spafford Ricci Art & Archival Conservation Inc.

Conservators mount the mosaics into new bronze frames using fresh concrete.

Credit: Fraser Spafford Ricci Art & Archival Conservation Inc.

Before conservation treatment, the Ornithology panel was dirty with lost mortar and tesserae.

Credit: Fraser Spafford Ricci Art & Archival Conservation Inc.

After conservation treatment, the panel is clean, degraded mortar and grout are removed and replaced, and missing tesserae are replaced.

Credit: Fraser Spafford Ricci Art & Archival Conservation Inc.

Replicate bronze frames, fabricated by Accurate Mechanical Systems, are pre-installed on a new wall in Brock Commons to display the restored mural.

Credit: Fraser Spafford Ricci Art & Archival Conservation Inc.

What does it mean to you to have the Thomas mural as part of the Belkin Art Gallery collection?

Melanie: The refurbished Lionel and Patricia Thomas mural (Symbols for Education) is an important modernist public artwork from 1958-60 that continues to have relevance to the ways in which we conceive of education and its changing fields of study at UBC.

The works in Belkin’s Outdoor Art Collection span a century and the Thomas mural holds an important place for the ways in which art has been commissioned at UBC to reflect on the processes of the university and how we can consider the fertile period of the 1950s-60s within modernist ideas and communications. The artists encouraged an interrelationship between the arts, particularly through visual arts and architecture, which was reflected in Lionel Thomas’s teaching in the departments of Fine Arts and Architecture.

“This public artwork is a reflection of its time, yet continues to speak through the decades. The Thomas mural articulates itself within ongoing change through its form—the networked symbols of faculties and departments—and through a history of the campus.”

How do artworks like the Thomas mural contribute to the UBC environment?

Julia: Two things struck me upon looking at Symbols for Education. The first is the esoteric quality of these symbols. Lionel and Patricia Thomas came up with a visual lexicon that is intelligible, yes, but also deeply idiosyncratic. What came to my mind initially was this moment in the 1940s and 1950s when artists were interested in mining the unconscious for archetypal symbols such as spirals, snakes, and the moon. There never seems to be this “one-to-one” relationship between a symbol and its meaning, though, and art historian Meyer Schapiro summarized this idea neatly in a 1948 Life magazine discussion: “I believe it is not paradoxical to say that it is precisely because the symbols are not completely legible that we value them.”

The second element that stood out to me was its diagrammatic quality. It is composed of rectangular blocks sutured with connecting lines. It seems as though the artists created this diagram of a university, an abstract representation of the stitched-together, shifting network of students, staff, faculty, departments, research, and publications that make up an institution. It can be easy to forget that an institution is not a ‘thing,’ but rather a series of social relations. It is significant that this work is being reinstated in what was once the social heart of the university. On campus, people routinely walk around, eat lunch at, and read underneath public artwork, and so I think it is weighty indeed as an expression of those very social relations.

Barbara: The individual panels that contribute to the holistic reading of Symbols for Education, can be conceived as a type of map or diagram – a Table of Contents of sorts that at the time of its making, provided a synopsis of what lay ahead. The panels carried the symbology that represented educational disciplines, with the spaces between them being almost as important as the subjects themselves.

“Whether seen from a distance or close up by those who passed by it daily or only upon occasion, this compelling artwork continued to impact the campus in meaningful ways for over six decades.”

Sarah: Generally speaking, public art is subjected to very aggressive conditions including harsh climate, physical blows, and public interventions. Mosaics are a very durable form of outdoor art being strong, inorganic, and stable in extreme climates. The restored Thomas mosaic sculpture will look very close to the original artwork because the artists were clever enough to choose an art form that can last decades and even centuries.

“To have the refurbished Thomas mural reinstalled on Brock Commons is an achievement in maintaining our complex histories and carrying these aesthetic and pedagogical conservations into contemporary discourse.”