A new collaboration has brought the UBC Department of History and the Museum of Vancouver together on an exciting pedagogical project, which centres on researching and exhibiting the MOV's South Asia collection.

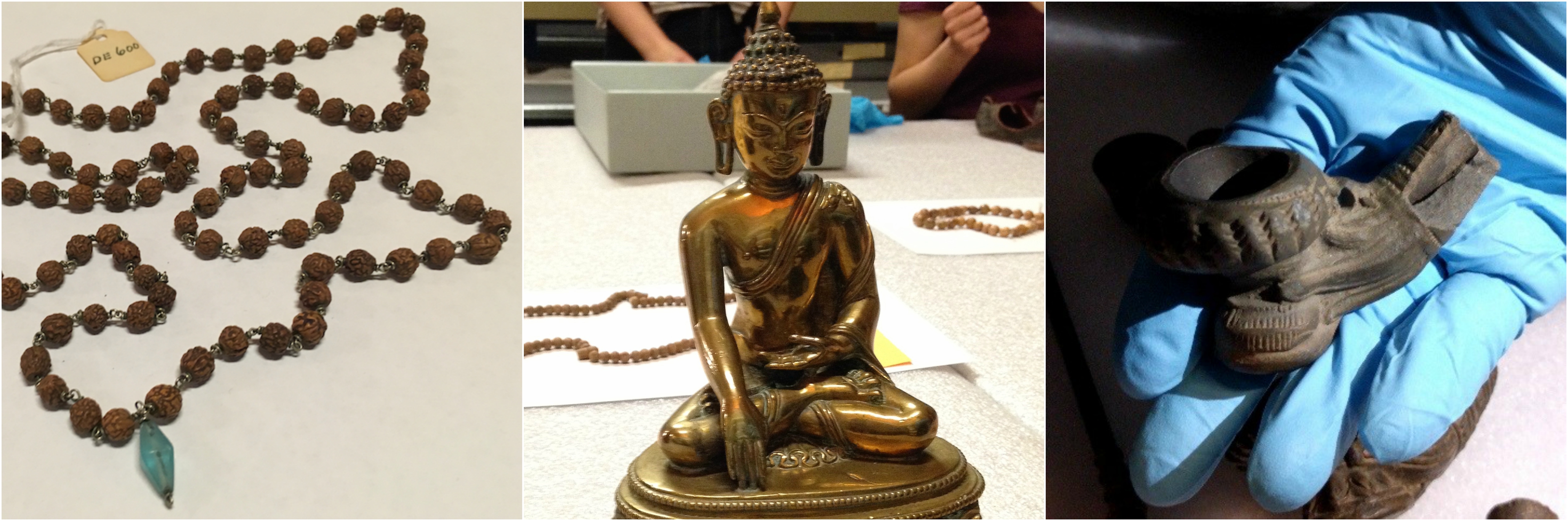

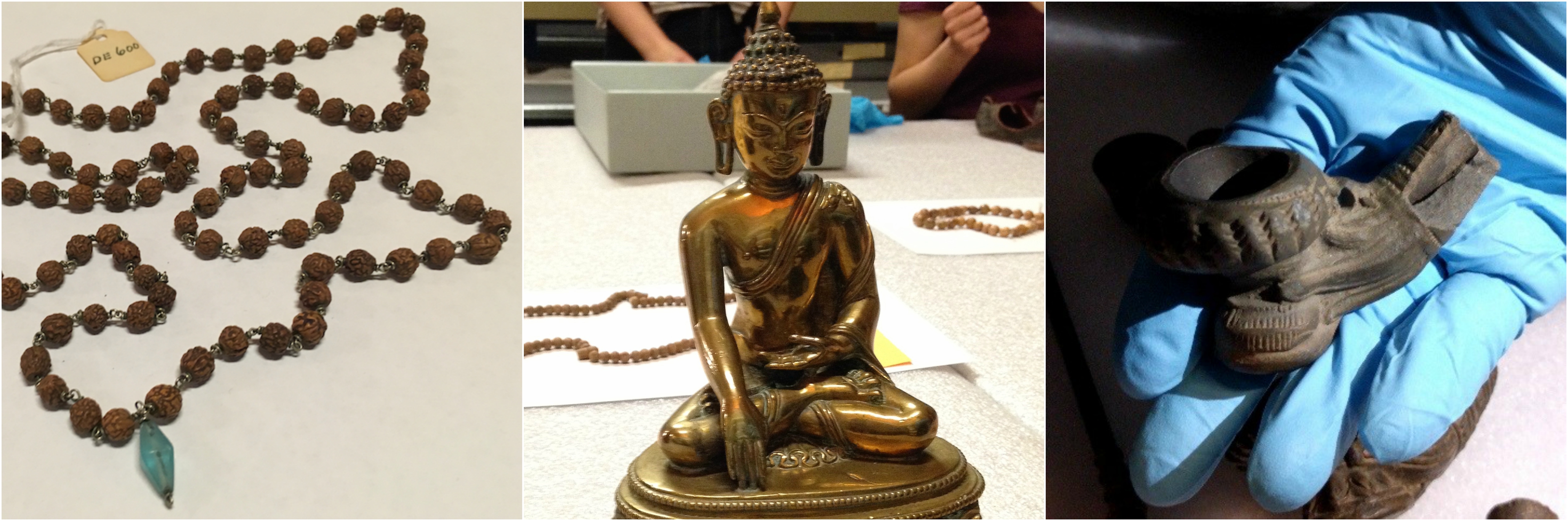

In 2014, the Museum of Vancouver approached UBC historian Tara Mayer for her insights on their collection of South Asian artefacts. The collection includes textiles, religious icons carved from metal and wood, intricate beadwork, prayer beads and a wealth of other curiosities that had been transported to Vancouver in the 1930s by local travellers. The collection was not extensively catalogued, it had never been exhibited, and little was known about the function or cultural significance of these objects.

As an expert in South Asian material culture, Mayer was well suited to provide context and research expertise on the provenance of these intriguing objects. But as she began to survey the items herself, she recognized an exciting opportunity to engage her students in the rigours and challenges of museum conservation. With support from Museum of Vancouver (MOV) curator Viviane Gosselin, and with funding from the Centre for Teaching and Learning Technology, Mayer developed a course entitled “Objects of Encounter: Local and Global Histories of South Asia at the Museum of Vancouver”.

The first iteration of the course in summer 2017 gave 20 UBC Arts students hands-on experience in cataloguing and conservation, in addition to classes on campus to establish historical context for the objects. Students participating in the upcoming 2018 session will develop curatorial skills in collaboration with MOV curators as they design a virtual exhibition.

We spoke to Mayer about the challenges and rewards of giving students a hands-on experience with the past.

Dr. Tara Mayer is a specialist in South Asian material culture.

Why did you create this course?

Working in the museum, archive, or heritage sector is an ambition held by many students who major in History. Finding opportunities for students to gain practical experience in these fields, however, is notoriously difficult. This course provides an opportunity to not only learn about material culture research and museum protocols in the abstract, but to directly apply these skills as part of their own, original work. In large part due to the richness of expertise amongst the curatorial and conservation staff at the MOV, it was possible to build an ambitious course that offers experiential learning in both the intellectual and pragmatic aspects of object-based, museum research.

Since joining the History Department five years ago, I have worked to broaden training in “visual literacy” amongst undergraduate History students, who we train extensively in textual analysis but not always in applying the same critical skills to visual and material sources of the past.

What did this course consist of? How were students exposed to the process of researching and cataloguing historical objects?

After providing students with a grounding in modern South Asian history (with a focus on migration and diaspora), we transitioned from the classroom into museum storage. There, students selected one object (or type of object) for their research project. Their task was to expand upon or, in many cases, develop for the first time a catalogue entry for their object, which was to provide information on its provenance, function, and cultural significance. The process of touching and looking at objects is such an important one, and students received training in how to formulate research questions based on their observations. From there, students embarked on independent research. They consulted knowledge-bearers in the local South Asian Sikh, Hindu, and Buddhist communities and had phone and email exchanges with academics and museum staff at other institutions in North America, Europe, and India.

What challenges did your class face?

This is an ambitious course in the sense that it asks students to work with diverse sets of skills related to historical analysis, object-centred research, and community engagement. To my surprise, it attracted students with backgrounds in Anthropology, Art History, International Relations, Political Science, Linguistics, and Asian Studies, to name a few. The challenge from my perspective was to cultivate particular methods of analysis amongst students from very disparate disciplinary backgrounds. From the perspective of the students, I think it was tough to fully digest the incompleteness and imperfection that accompanies our work as historians.

What did you enjoy most about this course?

Without question, I most enjoyed our time in museum storage, sharing in the enthusiasm and curiosity with which students selected and handled objects and learned to employ their senses. Rarely are students permitted such an intimate, tactile experience of the past.

The MOV’s South Asia collection includes textiles, religious icons carved from metal and wood, intricate beadwork, prayer beads and a wealth of other curiosities that had been transported to Vancouver in the 1930s by local travellers.

Student Perspective

Leigha Schjelderup

“As someone with little previous knowledge about the study of material culture or the internal operations of museums, I gained a lot of insight about each while working with the Museum of Vancouver’s wonderful team of curators. I felt extremely privileged to have had exposure to generations of the city’s material history while spending time in the MOV archives. This was complemented greatly by our class lectures and discussions back at UBC.

I feel I’m now armed with a new set of skills in historical analysis and critical thinking. Gaining the confidence to rely on my own senses during research–understanding them as valuable due to, and not in spite of, individual subjectivity–was a powerful experience. I quickly understood that the root of the course research project was much more about the process of learning how to explore material culture, rather than discovering groundbreaking conclusions about the object you choose to analyze.” – Leigha Schjelderup, participant in the 2017 session of History 390A.

The upcoming 2018 summer session is open to all students (the course schedule for summer 2018 courses comes out in January or February and registration opens in March). Participants will develop curatorial skills in collaboration with the team at MOV as they design a virtual exhibition of these materials, on the basis of research generated during the 2017 session.