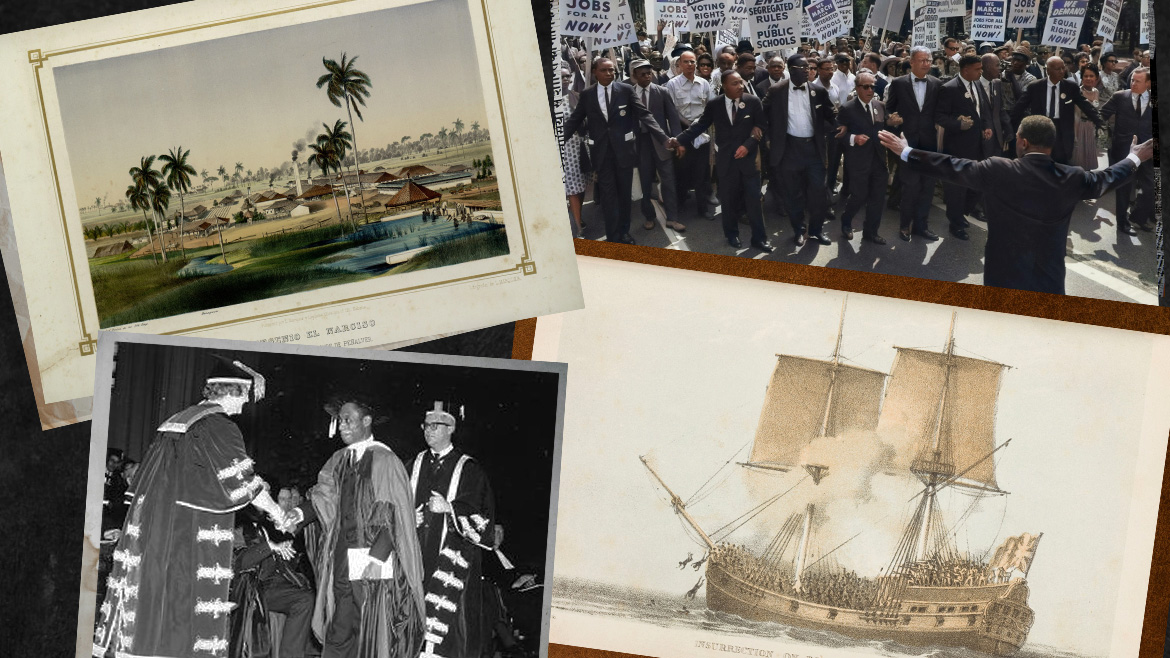

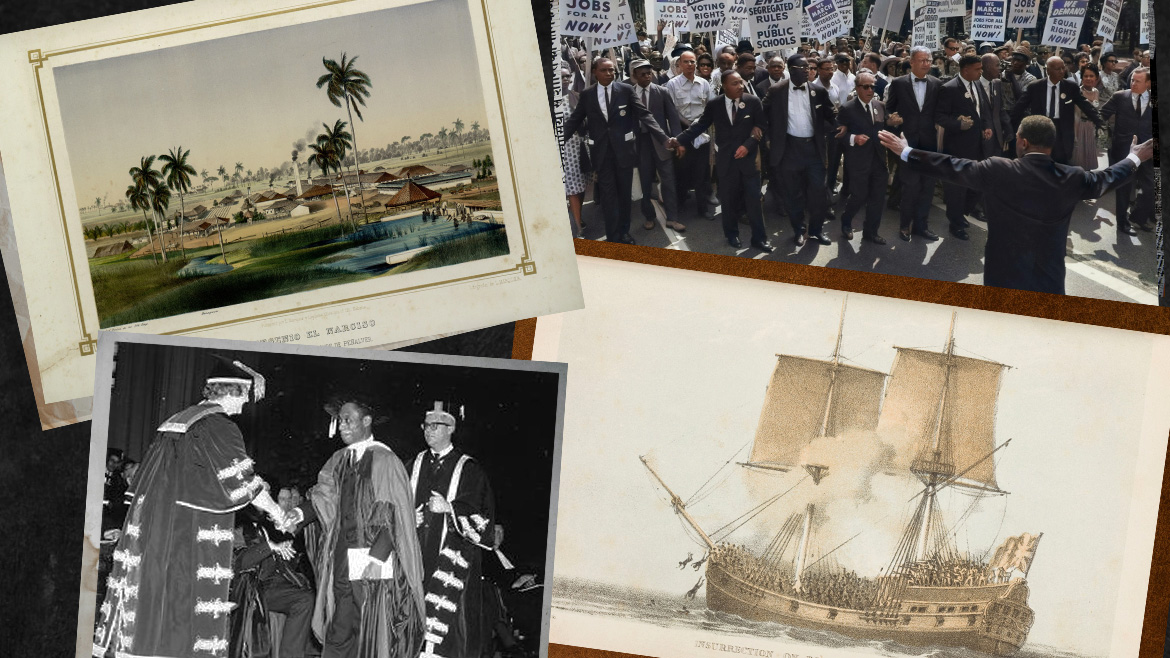

Images: The Sugar Mills of Cuba, 1850-1859 (upper left), Martin Luther King Jr. in the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, August 28, 1963 (upper right), James Baldwin receiving honorary degree, 1963 (bottom left), lithograph of a slave ship in London, 1851 (bottom right)

As we celebrate Black History Month, we recognize the crucial research that sheds light on the Black community’s rich history and exceptional achievements. Through research, we gain a comprehensive understanding and appreciation of Black history’s diverse perspectives and experiences. We are honoured to welcome Dr. Peter James Hudson to discuss his research on Black dispossession.

Dr. Peter James Hudson is an Associate Professor at the Department of Geography, with his studies focused on Black dispossession and resistance. Dr. Hudson’s research is rooted in the methodologies and literature of Black Studies, political economy, geography, and history. Specifically, he explores the long-standing histories of Black dispossession under capitalism and the resistance Black communities have put up in response.

The Faculty of Arts deeply values and appreciates the remarkable contribution that Black scholars, staff, and students have made to enhance our understanding of Black history and excellence. We spoke to Dr. Hudson to learn more about his research.

Dr. Peter James HudsonAssociate Professor in the Department of Geography

Peter James Hudson examines Black dispossession and resistance under capitalism through Black Studies’ literature and methodologies.

What are some of the most important ideas from your research?

My research examines the long histories of Black dispossession under capitalism – that is, the historical operations by which people of African descent are robbed of their land and labor, culture and souls – and Black resistance to capitalist dispossession. In practice, this means two interrelated things. First, as my book Bankers and Empire: How Wall Street Colonized the Caribbean demonstrates, I have been researching the histories of institutions of capitalism and imperialism that have shaped the conditions of modern Black life and history. In this case, I studied the foreign expansion of US financial institutions such as JPMorgan Chase and Citigroup into the early twentieth century Caribbean — Cuba, Haiti, the Dominican Republic, and Panama — as part of a project of US imperialist extension. I have also examined the history of Canadian institutions, including the Royal Bank of Canada and Scotiabank in the Caribbean.

Second, I am interested in how writers of African descent have examined the history of capitalism and colonialism, especially through the lines of political economy, in order to understand their histories and conditions of oppression under capitalism and colonialism. To that end, I have written on the work of writers, including Jamaica’s Claude McKay, Guyana’s Walter Rodney, South Africa’s Neville Alexander, and Lorenzo Kom’boa Ervin of the United States. I am currently doing an extended project on Trinidad’s George Padmore.

What lessons can people take away from your work?

First, the importance of understanding institutions — banks, insurance firms, corporations, law firms, and militaries — in shaping the political-economic, racial, and legal regimes of global white supremacy.

“Second, the importance of studying Black writers not as mere instantiations of Black identity or examples of the Black self, but because their work provides a methodology and a critique: who but the step-children of slavery, colonialism, imperialism, and white supremacy are better placed to understand the history of slavery, colonialism, imperialism, and white supremacy?”

Can you tell us about a specific moment in the long history of Black resistance to capitalist dispossession that you find particularly significant or compelling?

The Haitian Revolution (1791-1804): a thirteen-year revolt against slavery, white supremacy, and French, English, and Spanish colonialism that resulted in the birth of the Republic of Haitian. It is the second free republic in the Americas, the first free Black republic in the world, and the first place in the modern world where African people were free.

The example of Haiti inspired Black revolts against slavery throughout the Americas, as well as a long continuing history of repression and counter-revolution by the forces of white supremacy that have sought to destroy Black independence and sovereignty and preserve the power of the white plantocracy. All Black people are indebted to Haiti even as Haiti is still paying for its independence. As the great abolitionist Frederick Douglass stated during a lecture on Haiti delivered at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893, “Haiti is black, and we have not yet forgiven Haiti for being black or forgiven the Almighty for making her black.”

How do you see the field of Black Studies evolving and what advice would you give to students interested in this area of research?

It is impossible to say anything about the field of Black Studies evolving in the coming years. How can we talk about the future of Black Studies when Black Studies, in Canada at least, does not have a past?

I am not saying that no work in Canada fits under the rubric of “Black Studies.” Indeed, look at the footnotes to the introduction of a special issue of The CLR James Journal, ”On Black Canadian Thought,” that almost a decade ago, I co-edited with Professor Aaron Kamugisha of Smith College and the University of the West Indies. The footnotes demonstrate that there is a rich body of work from Canada that could be classed as Black Studies. However, historically, little of it (if any of it) was produced within Black Studies departments or programs, and much of this intellectual work took place outside of the university itself.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the United States experienced an explosion of programs, institutes, and departments, accelerated by the terrible assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. There was a corresponding level of financial support from institutions and foundations to hire Black professors and bring in Black students and create Black scholarly journals. In Canada, however, there has been no real, sustained Black Studies movement – and there is often no memory, institutional or otherwise, of earlier work by Black scholars and intellectuals in Canada, be it from a decade or a century. Indeed, few people know that in November 1963, the great African American writer James Baldwin was granted an honorary degree of letters by the University of British Columbia. More than six decades after the fact, what has UBC done to continue Baldwin’s legacy? Is Baldwin even taught here? Where are the fellowships or chairs or programs in his name?

“I would tell students several things. If you want proper funding and actual departments, you should look to the United States. If you wish to remain in Canada, you should be engaged in self-study groups and independent publishing that is not reliant on the university. You should excavate and draw on the local, national, and international histories and historiographies of Black Studies. If you stay here, students must make the demands of professors, departments, and universities for Black Studies.”