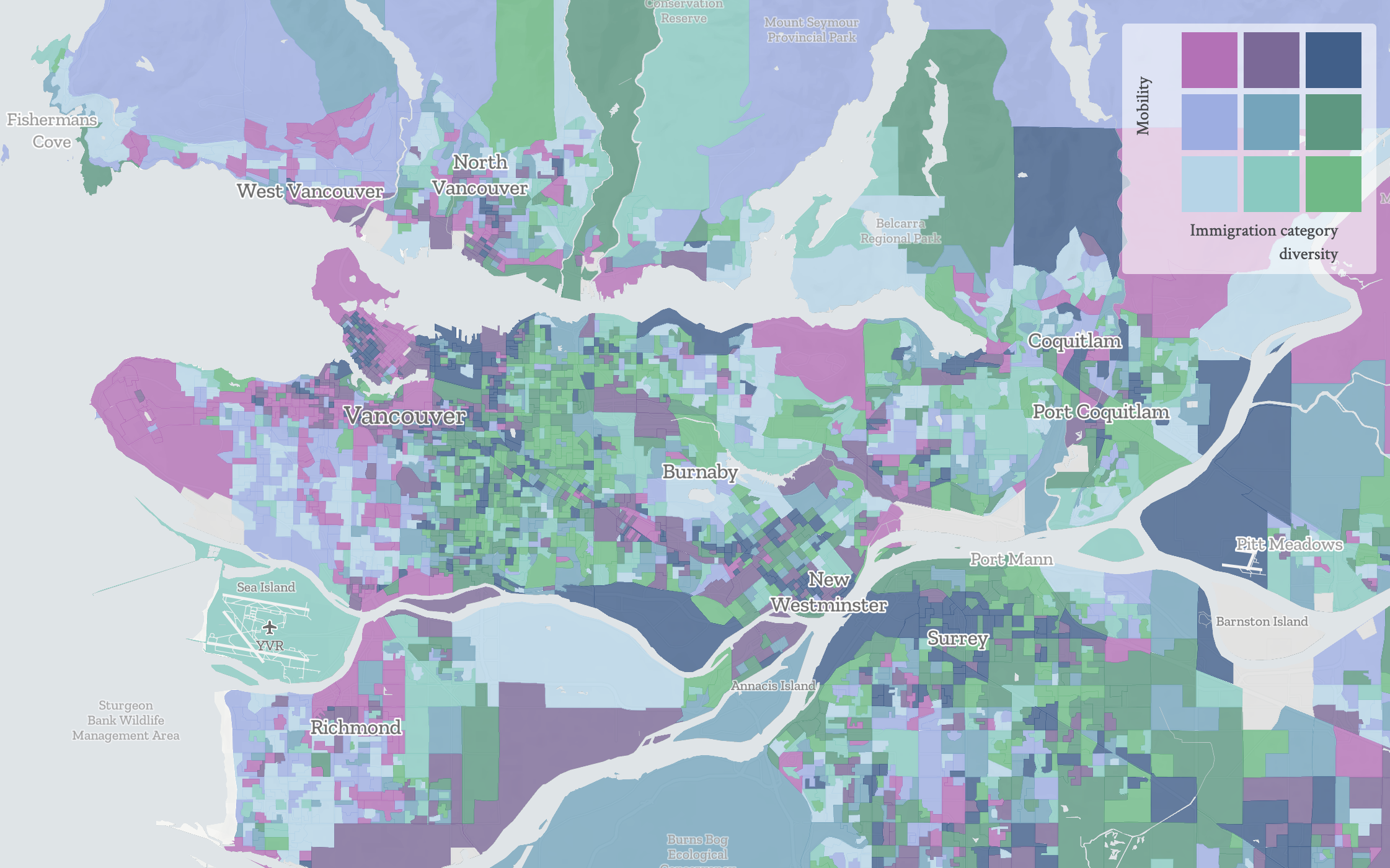

Prof. Daniel Hiebert

Daniel Hiebert is a Professor of Geography at UBC who specializes in immigration policy and the integration of newcomers into Canadian housing and labour markets. Prof Hiebert also examines the consequences of the growing ‘super-diversity’ of Canadian society and often serves in advisory roles for government agencies and non-governmental organizations. In our Q&A, Dr. Hiebert touches on how best to support refugee populations and the most common misconceptions about the international refugee crisis.

What are the biggest misconceptions about the international refugee crisis?

- That refugee issues are mostly ‘solved’ by affluent, powerful countries, when the reality is the vast majority of refugees are hosted in the Global South, typically in countries adjacent to failing states and conflict zones.

- That migrants can be neatly divided between refugees fleeing persecution and those moving for economic or family reasons. Vast numbers of migrants relocate for a combination of reasons that include personal safety and failing economic livelihoods. The international Refugee Convention does not acknowledge this complexity and therefore its signatory countries (such as Canada) do not have to either.

- That refugees who travel ‘illegally’ have broken laws and therefore don’t deserve protection. The Refugee Convention is very specific on this point and stipulates that governments are not allowed to take the means of travel (legally documented vs. clandestine and without permission) into consideration when they decide whether to offer a person protection.

- That all human smugglers are criminals preying upon the weak, making mega-profits out of human misery. This is sometimes true (it is widely believed, for example, that organized crime has turned its attention to human smuggling, in many countries), but also often false. Many human smugglers are family members, members of faith communities, and/or small-scale entrepreneurs. As in all things, there are good and bad people conducting human smuggling operations.

What is your opinion on the Canadian government’s response to the crisis?

Generally good. I appreciate the comprehensive approach being taken, with money donated to the UNHCR to support refugees hosted in countries near Syria, as well as the significant relocation program that has been created. In my opinion, this represents a fair balance in terms of exercising Canada’s international responsibility. It is also worth noting that the political climate for refugees is far more open in Canada than south of the border, in part because prominent Canadian politicians and public officials (e.g. the Prime Minister, the Commissioner of the RCMP, the Director of CSIS) have issued careful statements supporting the processes Canada has adopted.

The tricky issue, though, is the facilitation of good settlement outcomes, which is very expensive and also fraught with complex equity dilemmas. For example, refugees entering places like Vancouver face extreme challenges securing adequate accommodation. But this is also true of MANY low-income residents of Vancouver. It would of course be wonderful for a housing strategy to deal with this challenge universally, but in the absence of that, should refugees be given extra resources to pay for housing, lessening the supply for others in critical need? Canadians have yet to resolve this pressing issue, which is really about the overall nature of social inequality in Canada, which forms the context for refugee resettlement.

How has your research informed the current refugee crisis?

My research is mainly about Canada’s role in refugee issues (through policy) and the settlement and integration of refugees in Canada. On the former, as everyone knows, the recently elected national government placed a much higher priority on refugee issues than the past one (which often implied that refugees represent a threat to national security). It is important, though, to acknowledge that Canada’s current efforts, which will likely bring more than 50,000 Syrian refugees here, constitute only a small fraction of a real solution.

On the latter point, it is clear that the broad outcomes of the settlement and integration process have a significant influence on Canada’s policy climate. That is, national policy will be more open to admitting more refugees if those who come to Canada have positive settlement and integration experiences. Conversely, should these experiences be negative (and there is much debate over what that means and how it might be measured), we can expect to see less generosity in the future. This means that anyone who wants to see Canada exercise more international humanitarian responsibility and admit larger numbers of refugees, ought to consider how to foster positive settlement outcomes.

MORE: Watch Part 1 of the Liu Institute for Global Issues video series Seeking Refuge, featuring an interview with Professor Hiebert.