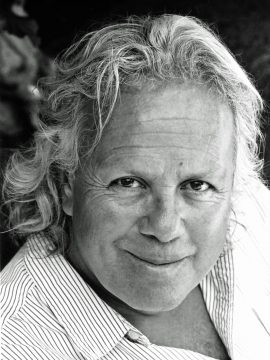

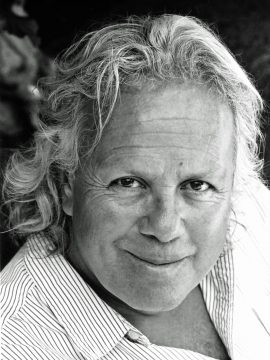

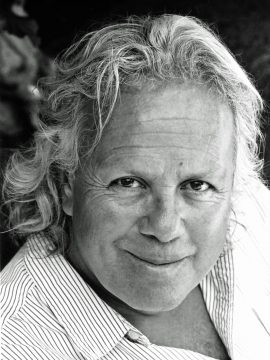

Charles Wilkinson

Charles Wilkinson has been working as a filmmaker for 30 years. He’s worked on feature films, network TV movies, and episodic shows. After taking a break to study film production at UBC, he shifted his focus to documentary feature films. His feature documentary Haida Gwaii: On the Edge of the World (2015) won the Most Popular Documentary at VIFF, Best Canadian Feature Documentary at Hot Docs, and the Director’s Guild Allan King Award. On October 1st he’ll premiere Haida Modern at VIFF, his latest feature documentary, which profiles the Haida artist Robert Davidson. Charles spoke to Arts via phone.

Over your 30 year career, you largely worked on TV shows and feature films before your MFA in 2008. Since then you’ve shifted to focusing on documentary. What draws you to the documentary format?

I started out in documentary. For about 10 years I was a hippie and lived in the woods. [Then] I went to a student film show. I think it was at UBC. The technology had changed so much in a relatively short period of time. I thought, “Wow, I’d love to do that.”

I went to the [National] Film Board and talked to Peter Jones, the executive producer at the time, and he said, “If you’re interested in documentary, go to SFU. If you’re interested in drama, go to UBC.” So I went to SFU.

[Then] there was a national commission that travelled across the country looking into the state of Canadian media. What they concluded was that documentary was dead, and that the only relevant medium for Canadian film would be drama. They promptly reduced the funding of the Film Board and started pouring cash into the Canadian Film and Development Corporation, which became Telefilm.

That was very difficult to resist when we’d been eking out a living on tiny little Film Board projects. I did the dramas for all those years and it was great, it was relatively well paying. But then I started losing interest like crazy. Every script that came in the door was stupider. I got tired of it.

When Sharon McGowan [associate professor at UBC] raised the idea that maybe I could go and study at UBC, I just jumped at the chance. Sharon really encouraged me to reinvent my career. The studying I did there let me take a deep breath and realize what I wanted to do all along.

Haida Modern, which will receive its world premiere at VIFF, profiles the artist Robert Davidson. How did you first meet Davidson and what made you want to create a feature documentary on him?

We made the feature Haida Gwaii: On the Edge of the World and during the time we were filming there we met Robert [and he] kindly agreed to let us use some of his art in the show. I was beyond thrilled because I’ve been an admirer of Roberts work, really, my whole adult life. What I realized was that the worldview that he was presenting was one that I’ve been in sync with for a long time.

When the first entrepreneurs came here from Europe in their sailing ships, they were so anxious to get their hands on the material wealth that they ignored the most valuable thing they could have found here, which was a worldview that would allow them to live here relatively sustainably, more or less forever.

A good story is always a sympathetic hero, on a vital quest, against insurmountable obstacles. Robert is all of those three things in spades. He’s enormously sympathetic. His vital quest to restore and bring back to life Haida culture was a matter of survival for an entire people. And the obstacles were beyond insurmountable, and yet the success is showing every day.

You already had experience before starting your MFA. How did it help set you up for the next ten years of your career?

For a long time as a young filmmaker, you’re just so honoured that anybody would pay you money to make a movie. It takes quite a while to really take a step back and figure out, “Is this really what I want to be doing?” That was the fundamental thing that taking that break at UBC allowed. I studied some of the great masters of cinema and saw how they dealt with that same issue. The reason we were studying them was that they made the right decision, they turned their back on the money and the easy stuff and they did what they felt. I couldn’t help but think: this is what I want to do.

What challenges have you faced in your 30 year career?

Being a filmmaker, it takes every ounce of every bit of ability you have in every area, all the time. To use a car analogy… imagine that you’ve got your foot on the floor and you’re going around a sharp curve at all times.

I’ve always strived to understand everything about the technology so I can direct intelligently. I found that by being technical… that allowed me to direct competently and it’s given me the ability to do all of those jobs. Today, when we make a movie—when I say “we” I mean my wife and partner Tina Schliessler and me—I pretty much do all of those jobs: writing, finance, shooting, recording sound, sound editing, scoring, everything—we even usually make our own posters. That came from years of studying the people around me and learning what they did.

It allows you to make movies for a lot less money. What that’s meant is that we’ve financed them quicker. We turned this one around in a year, from the first pitch to premiere was a year and two months. That’s why the shows tend to look like we spent a lot more money than we did. You can actually make these really personal movies without having a bunch of white trucks following you around.

What advice would you give to students and alumni interested in breaking into the industry?

[Everybody has] an uncle who’s really gregarious and when you have Thanksgiving dinner, that guy tells stories and everybody laughs. That guy would make a good filmmaker. But if you’re somebody who’s shy and retiring and see yourself as somebody who works alone quietly—that’s what poetry is for. I can’t overstress how social filmmaking is. You’re constantly talking. If you’re not a people person who really lives by words, it’s going to be really hard to get anywhere.

The idea that there’s something glamorous about this work… honestly, I’ve been doing this for a long time and I don’t recall any feeling of anything close to glamour. The people who are the happiest in this are the people who love to tell stories and who would do it whether they got paid or not.

Your feature documentary, Haida Gwaii, won the Most Popular Documentary at VIFF, Best Canadian Feature Documentary at Hot Docs, and the Director’s Guild Allan King Award. What are your hopes for Haida Modern?

Steve Buscemi, in Living in Oblivion, dreamt of getting an award where they said, “This was the best movie ever made in the history of movies.” Of course! Honestly, I never know what to expect. I know that this film is technically and artistically superior… It’s my best work. I’m so proud of it and it’s been such a pleasure to work on it, in large part because Robert was such a great person to work with. But I don’t know, it would be great if people would see it.

Knowledge Network has been keen to finance our last four or five films… their audience is really huge in BC and all across Western Canada, and those people really seem to like the work that we do. They’re so appreciative. I love that audience. I’m just hoping we don’t let them down.

Charles Wilkinson

Charles Wilkinson has been working as a filmmaker for 30 years. He’s worked on feature films, network TV movies, and episodic shows. After taking a break to study film production at UBC, he shifted his focus to documentary feature films. His feature documentary Haida Gwaii: On the Edge of the World (2015) won the Most Popular Documentary at VIFF, Best Canadian Feature Documentary at Hot Docs, and the Director’s Guild Allan King Award. On October 1st he’ll premiere Haida Modern at VIFF, his latest feature documentary, which profiles the Haida artist Robert Davidson. Charles spoke to Arts via phone.

Over your 30 year career, you largely worked on TV shows and feature films before your MFA in 2008. Since then you’ve shifted to focusing on documentary. What draws you to the documentary format?

I started out in documentary. For about 10 years I was a hippie and lived in the woods. [Then] I went to a student film show. I think it was at UBC. The technology had changed so much in a relatively short period of time. I thought, “Wow, I’d love to do that.”

I went to the [National] Film Board and talked to Peter Jones, the executive producer at the time, and he said, “If you’re interested in documentary, go to SFU. If you’re interested in drama, go to UBC.” So I went to SFU.

[Then] there was a national commission that travelled across the country looking into the state of Canadian media. What they concluded was that documentary was dead, and that the only relevant medium for Canadian film would be drama. They promptly reduced the funding of the Film Board and started pouring cash into the Canadian Film and Development Corporation, which became Telefilm.

That was very difficult to resist when we’d been eking out a living on tiny little Film Board projects. I did the dramas for all those years and it was great, it was relatively well paying. But then I started losing interest like crazy. Every script that came in the door was stupider. I got tired of it.

When Sharon McGowan [associate professor at UBC] raised the idea that maybe I could go and study at UBC, I just jumped at the chance. Sharon really encouraged me to reinvent my career. The studying I did there let me take a deep breath and realize what I wanted to do all along.

Haida Modern, which will receive its world premiere at VIFF, profiles the artist Robert Davidson. How did you first meet Davidson and what made you want to create a feature documentary on him?

We made the feature Haida Gwaii: On the Edge of the World and during the time we were filming there we met Robert [and he] kindly agreed to let us use some of his art in the show. I was beyond thrilled because I’ve been an admirer of Roberts work, really, my whole adult life. What I realized was that the worldview that he was presenting was one that I’ve been in sync with for a long time.

When the first entrepreneurs came here from Europe in their sailing ships, they were so anxious to get their hands on the material wealth that they ignored the most valuable thing they could have found here, which was a worldview that would allow them to live here relatively sustainably, more or less forever.

A good story is always a sympathetic hero, on a vital quest, against insurmountable obstacles. Robert is all of those three things in spades. He’s enormously sympathetic. His vital quest to restore and bring back to life Haida culture was a matter of survival for an entire people. And the obstacles were beyond insurmountable, and yet the success is showing every day.

You already had experience before starting your MFA. How did it help set you up for the next ten years of your career?

For a long time as a young filmmaker, you’re just so honoured that anybody would pay you money to make a movie. It takes quite a while to really take a step back and figure out, “Is this really what I want to be doing?” That was the fundamental thing that taking that break at UBC allowed. I studied some of the great masters of cinema and saw how they dealt with that same issue. The reason we were studying them was that they made the right decision, they turned their back on the money and the easy stuff and they did what they felt. I couldn’t help but think: this is what I want to do.

What challenges have you faced in your 30 year career?

Being a filmmaker, it takes every ounce of every bit of ability you have in every area, all the time. To use a car analogy… imagine that you’ve got your foot on the floor and you’re going around a sharp curve at all times.

I’ve always strived to understand everything about the technology so I can direct intelligently. I found that by being technical… that allowed me to direct competently and it’s given me the ability to do all of those jobs. Today, when we make a movie—when I say “we” I mean my wife and partner Tina Schliessler and me—I pretty much do all of those jobs: writing, finance, shooting, recording sound, sound editing, scoring, everything—we even usually make our own posters. That came from years of studying the people around me and learning what they did.

It allows you to make movies for a lot less money. What that’s meant is that we’ve financed them quicker. We turned this one around in a year, from the first pitch to premiere was a year and two months. That’s why the shows tend to look like we spent a lot more money than we did. You can actually make these really personal movies without having a bunch of white trucks following you around.

What advice would you give to students and alumni interested in breaking into the industry?

[Everybody has] an uncle who’s really gregarious and when you have Thanksgiving dinner, that guy tells stories and everybody laughs. That guy would make a good filmmaker. But if you’re somebody who’s shy and retiring and see yourself as somebody who works alone quietly—that’s what poetry is for. I can’t overstress how social filmmaking is. You’re constantly talking. If you’re not a people person who really lives by words, it’s going to be really hard to get anywhere.

The idea that there’s something glamorous about this work… honestly, I’ve been doing this for a long time and I don’t recall any feeling of anything close to glamour. The people who are the happiest in this are the people who love to tell stories and who would do it whether they got paid or not.

Your feature documentary, Haida Gwaii, won the Most Popular Documentary at VIFF, Best Canadian Feature Documentary at Hot Docs, and the Director’s Guild Allan King Award. What are your hopes for Haida Modern?

Steve Buscemi, in Living in Oblivion, dreamt of getting an award where they said, “This was the best movie ever made in the history of movies.” Of course! Honestly, I never know what to expect. I know that this film is technically and artistically superior… It’s my best work. I’m so proud of it and it’s been such a pleasure to work on it, in large part because Robert was such a great person to work with. But I don’t know, it would be great if people would see it.

Knowledge Network has been keen to finance our last four or five films… their audience is really huge in BC and all across Western Canada, and those people really seem to like the work that we do. They’re so appreciative. I love that audience. I’m just hoping we don’t let them down.