Sociology Professor Lindsey Richardson has received a $1.2 million grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research to address the health impacts of socioeconomic marginalization among people who use illicit drugs.

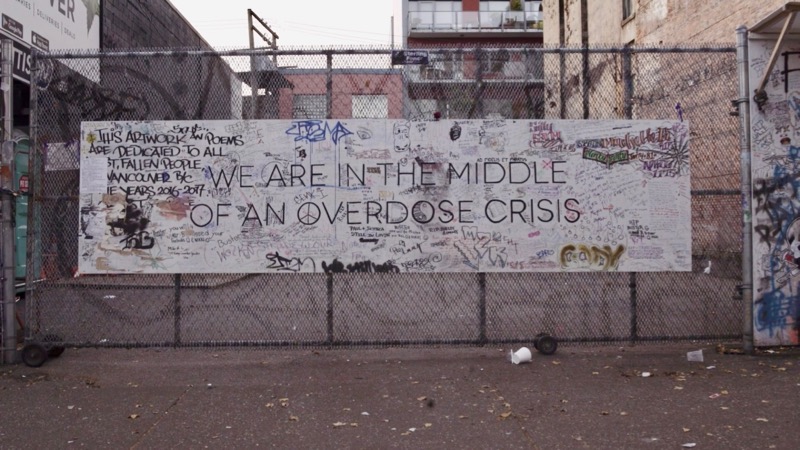

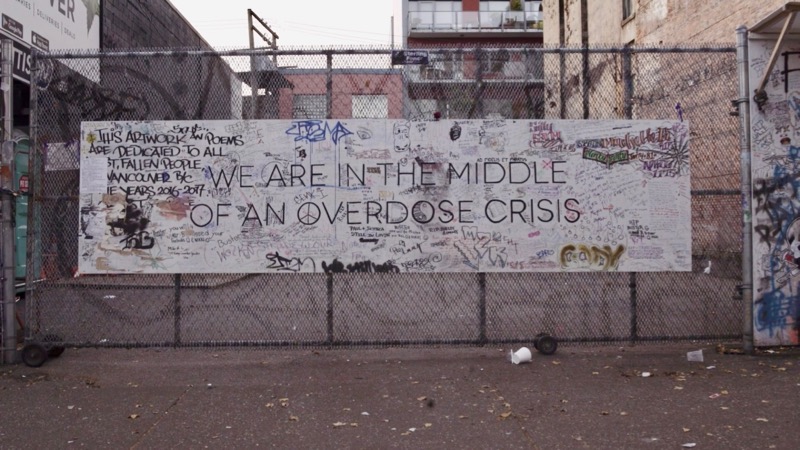

Nearly 2,000 people have died of illicit drug overdoses in B.C. since the province declared a public health emergency two years ago. The crisis is growing; the number of fatal overdoses in 2017 almost doubled the previous year’s total.

Health professionals are responding to the crisis with drug testing and overdose response facilities, but sociologist Lindsey Richardson has a different approach. She is experimenting with socioeconomic interventions to reduce drug use and related harm. She says it’s critical to address underlying socio-economic conditions like severe poverty and lack of housing to effectively respond to the overdose crisis.

Richardson, who worked on health and drug policy for the federal government before returning to academia, recently received a $1.2 million grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research to address the health impacts of socioeconomic marginalization among people who use illicit drugs. “My overall goal is to reduce drug use and related harm through effective interventions,” she says.

The Cheque Day Study

Dr. Lindsey Richardson

One example of such an intervention is her “Cheque Day” experiment, which varies the timing and frequency of income assistance payments among a group of people who use drugs. Currently, most communities in Canada and the United States deliver income-assistance payment once a month, on the same day for everyone.

“If you’ve ever been to the Downtown Eastside around income assistance payment day— ‘Welfare Wednesday,’ as it’s known in the neighbourhood— it feels like a characteristically different place,” says Richardson. “People get their money, they go and pay bills, they might pay off drug debts, they might replenish their food supplies.”

But that heightened level of activity also translates to more harm. “It’s not just fatal and non-fatal overdoses [that spike around cheque day], it’s also police service calls, incidents of violence, entering detox, emergency department admissions, mental health apprehensions by police.”

A collaboration between Richardson and the B.C. Centre for Disease Control documented a 40 per cent increase in fatal overdoses on the days following assistance payments.

Richardson believes the cheque day effect is a result of both individual and social triggers. “We all increase our consumption when we get paid, whether it’s groceries or shoes,” she says. “People who use drugs have that too.”

The social cues come from everybody in the community getting paid at the same time on the same day, says Richardson. “Who hasn’t gone out for a drink on pay day and had more than anticipated because they were having a good time, or having good social interactions that prompted them to order more alcohol than they were planning? The same thing happens with other substances.”

Interventions in Employment Models

Richardson is also researching other types of interventions, like access to economic opportunities. She says people who use drugs face significant barriers to traditional employment, and may rely on informal or prohibited forms of income generation or risky financial management strategies. This may include criminal activity like drug dealing or sex work, or being forced to engage with predatory lenders and accumulating drug debt— activities that can perpetuate further harm.

Her team wants to examine whether participating in flexible and innovative employment opportunities can interrupt cycles of unemployment, prohibited income generation and related harm. One such model is EMBERS Eastside Works, a new economic development hub initiated by the City of Vancouver that facilitates low-barrier income opportunities for people who are not ready to enter the formal labour market.

By collaborating with Eastside Works, and scientifically evaluating interventions for potential economic, social and health impacts, particularly for people who use drugs, Richardson is hoping to translate innovation into program and policy changes that benefit vulnerable populations in B.C. and across the country.

“I’m honoured and feel really humbled to have been given the support to do this work,” she says. “I think it’s timely given the overdose crisis that is unprecedented in its scale.”

On April 19, Richardson and three other UBC experts will discuss “Drug Use and Addiction in the 21st Century” at UBC Robson Square.

The panel event is presented by UBC Faculty of Medicine, Faculty of Dentistry, Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, and Faculty of Arts, in partnership with alumniUBC.

Related Articles

- Lindsey Richardson and Jenna Van Draanen, “How to stop overdoses? Prevent them to begin with.” The Conversation. January 11, 2018.

- Lindsey Richardson, “The downsides and dangers of ‘cheque day’.” The Globe and Mail. March 24, 2017.

The Cheque Day Study is funded by:

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR)

- Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research (MSFHR)

- Providence Health Care Research Institute (PHCRI)

- Peter Wall Institute for Advanced Studies