Although Anne of Green Gables remains the most famous Canadian book in Japan, a recently released Japanese translation of The Cambridge History of Canadian Literature will connect Japanese audiences to a complete history of Canadian writing.

When a Japanese translation of Anne of Green Gables was released in 1952, it quickly became a literary sensation. The book struck a chord with Japan’s post-World War II audiences, became part of the national school curriculum and spawned dozens of Japanese adaptations, including an anime series, a musical and a theme park. Every year, thousands of Japanese tourists make a pilgrimage to Prince Edward Island to pay homage to author Lucy Maude Montgomery’s beloved 1908 story.

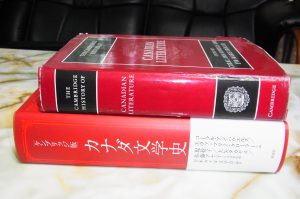

More than 60 years after “red-haired Anne” first made a splash in Japan, a Japanese translation of The Cambridge History of Canadian Literature has been released, entitled Kemburijji-ban Kanada Bungakshi. The translation connects Japanese audiences to a complete history of Canadian writing featuring works by Indigenous, francophone and multicultural authors, including Japanese-Canadian writers. The project – published this past August as an 830-page volume – took four years and 26 translators to complete, with Toshiko Tsutsumi, Takayasu Oya, and Ayako Sato as general editors.

The foreword to the translation is authored by the editors of the original volume – Professor Eva-Marie Kröller (UBC Department of English) and Coral Ann Howells (Professor Emerita, University of Reading; Senior Research Fellow, Institute of English Studies, University of London). Kröller and Howells underline the popularity of Canadian literature in Japan and celebrate the resulting promotion of research in Canadian literature by and for Japanese scholars and students.

- Read More: In 2009, Dr. Eva-Marie Kröller and Dr. Coral Ann Howells were interviewed by the UBC journal Canadian Literature about their experiences editing the original volume: “Editing the Cambridge History of Canadian Literature.”

- Read More: In November, 2016, the General Editors of the Japanese version of the Cambridge History of Canadian Literature outline the purpose of the translation and explain some of the challenges: “Not-so-Lost in Translation – Canadian Literature in Japan.”

In 2014, Professor Yukiko Toda, one of the translators, spent a term at UBC and was interviewed by ArtsWire about her views on Canadian literature and her contribution to the project.

The Japanese translation of The Cambridge History of Canadian Literature took four years and 26 translators to complete. It was published in August 2016.

__________________________________

Japanese scholar visits UBC to study Canadian literature

Originally published in ArtsWire in February 2014, this interview was lightly edited from the original.

Professor Yukiko Toda is a member of the Canadian Literary Society of Japan, the only Japan-based organization dedicated to the study of Canadian literary works. Prof. Toda has been visiting UBC’s Vancouver campus since Spring 2013 to research and translate Canadian literature into Japanese.

An associate professor of English literature at Sugiyama Jogakuen University in Nagoya, she is one of a team of Japanese scholars who are translating the Cambridge History of Canadian Literature (Cambridge University Press, 2009), ed. Coral Ann Howells and UBC English professor Eva-Marie Kröller. Professor Toda’s work involves translating a chapter on Canadian authors Alice Munro, Margaret Atwood, Carol Shields and Mavis Gallant.

ArtsWIRE: Canadians are always delighted when the international community celebrates our culture. What is it about Canadian literature that interests Japan’s scholars?

Toda: One of the things that draws scholars in Japan to Canadian literature is probably its unique position. It is influenced by British, American, and French literature, … and yet its particular sociopolitical, historical, and geographical landscapes produce something unique and different.

Many scholars are also drawn to Canadian fiction that deals with various issues that arise in a multi-ethnic society — identity politics, location/dislocation, belonging/not belonging, etc. Interest in immigrant stories as well as experimental fiction that portrays worldviews of a specific ethnic culture, and fiction written by First Nations writers arose in Japan after the traditional literary canon in North America was questioned and redefined in the 1970s. The civil rights movement in the U.S., feminism … , multicultural policy in Canada … led to the reframing of the literary canon, [and] also affected the study of English literature in Japan that had until then focused mainly on American and British literature. More scholars started to focus on ethnic minority and women’s writing, and also on the literature of other English-speaking nations including Canada.

These developments … led us to such questions as: Why do we study mainly British and American literatures and not literature from other parts of the English-speaking world? Why do we study English literature in Japan and what does it mean to us? Personally, these questions generated interest in Canadian literature which depicts various frictions that arise when different world views come into contact. In today’s world where the English language and Western thought are prevalent, studying various literatures written in English is one way for me to understand what is happening around the globe, and to seek possible ways for co-existence and a better world.

ArtsWIRE: Does Canadian literature have any unique qualities or traits that aren’t found in British or American literature?

Toda: Canadian critics have used terms such as “survival” and “garrison mentality,” in an attempt to define “Canadianness” that differs from both Britain and the States, and I think it is precisely this continual search for a non-British/American/French literature that is unique in Canadian literature.

The most famous Canadian book in Japan, Lucy Maud Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables, is no exception. Another translation recently came out in Japan by Yuko Matsumoto with notes on the plethora of literary allusions that the book contains — from Shakespeare, Scottish literature, and American literature. Yet, what is interesting about the book is that Montgomery portrays a character who is different from English or American characters — Anne insists that “a rose in any other name would not smell as nice,” and she cuts her hair not for a worthy cause like Jo in Little Women, but for having dyed her hair green.

Contemporary writers continue to search for stories written from a non-American, or non-Eurocentric subjectivity. The Japanese-Canadian author, Hiromi Goto, for instance, says that Canadian fantasy and science fiction need to “move beyond vampires, hobbits, and witches,” and introduce a person to see the world in different ways from those that are already inscribed in Canadian popular culture and education. Yet it is difficult to point out exactly the unique quality of Canadian literature because it is so diverse.

Yukiko Toda is an Associate Professor of English Literature in the Department of Foreign Studies at Sugiyama Jogakuen University in Nagoya, Japan.

ArtsWIRE: What would you say is your favourite book by a Canadian author and why should other Canadians read it?

Toda: I do want to recommend Joy Kogawa’s Obasan, a story of the Japanese Canadian internment camp and relocation during WWII … The book is well-known among scholars in Japan, and it is praised, not only for its historical significance as a text that prompted the Redress movement in Canada, but also for effectively capturing the aesthetic of Japanese language and culture. In the aesthetic of the subtle Japanese language silence represents just as much meaning and significance as the language of speech.

Western critics often view this novel as a “bildungsroman” (coming-of-age story) of the protagonist who moves from silence to speech whereas Japanese critics tend to read it as a story where the protagonist understands the depth of meaning behind “silence.” I find the difference in such interpretations extremely interesting.

The novel reveals an aesthetic based on high-context Japanese culture, which is very different from most Western cultures that favour direct speech and consider silence as a lack of self-assertion and interest.

“Shikataganai” (there is nothing we can do, it can’t be helped), “gaman” (to persevere with dignity), two terms that appear repeatedly in the novel, are untranslatable because they embody a cultural ethos deeply rooted in our culture and worldview. Non-Japanese readers often consider this negatively, saying it is merely giving up, instead of rebelling; for Japanese readers, it is a culturally specific expression, which means to accept their fate and persevere with dignity for the sake of their children and the community.